A one-time gang member in Los Angeles is taking his understanding of his community, his idealism and his knowledge of restorative practices back into neighborhoods to help gang members learn to change and be more positive community members. Carlos Alvarez, center, with two boys

Carlos Alvarez, center, with two boys

“Lots of kids embedded in gangs, their emotional intelligence is very minimal,” he says. “We have to build capacity around affect regulation.”

Carlos Alvarez, an IIRP licensed trainer, says restorative practices builds emotional connections and allows children to develop healthy social skills. This involves allowing students to process their emotion and trauma, which they often experience as physical symptoms, such as a tingling sensation in their hands when they get angry. “Ours is a bottom up approach to behavior,” he says.

In his role as Director of Student Discipline at Bright Star Secondary Charter School, a public charter school in south Los Angeles, Alvarez says he conducts five to six restorative conferences per week around issues like fights and class disruption that might previously been handled with suspensions.

He recalls one student he developed a long-term relationship with. His father was addicted to heroin and had abandoned his family. Like many children who have experienced trauma, this boy felt a lot of shame and believed there was no hope for the future. He lacked trust and his whole nervous system was highly reactive.

In school, the boy stole a teacher’s wallet containing $600 in cash – she had just been paid. Alvarez decided to attempt a restorative conference. He instilled a sense of safety and a desire to listen to the boy during a pre-conference meeting. In the conference, it came out that the teacher really liked the boy, and they had established a relationship. Alvarez asked the boy why he had betrayed her this way. He answered, “I knew she would eventually move out of my life. This was my way to get her out of my life first.”

Alvarez and the teacher were heartbroken to hear this, but they stayed emotionally connected with the boy. Alvarez commented, “When a child is extremely hurt, and there’s trauma in that hurt, the child will ask for help in the most disgusting ways. When their tone is intensifying, they’re actually asking for help. When they say f*** you, you have to lean into that. That’s what I do.”

Through the conference, the boy began to understand how his actions hurt the teacher. Two hours later, on his way home, the boy had a panic attack right out on the street. He threw up and the paramedics came. Alvarez says that sometimes the emotional impact of a conference is so great there’s a physical response. He added, “The boy never gave me a cheesy, ‘I will never get in trouble again.’ But he never did. He eventually graduated from high school.”

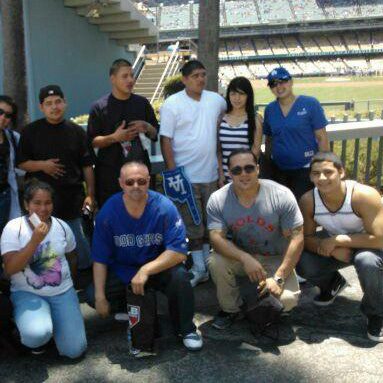

On a field trip to a Dodger's game.Alvarez acknowledges that in many ways gang culture is embedded in Latino culture in the city. But he says the vast majority of youth participate for social reasons and only stay in gangs an average of two years. The ringleaders — the so-called “five percenters” — average seven years and commit most of the anti-social acts and crimes associated with gangs. Alvarez believes restorative practices can reach both categories of gang member.

On a field trip to a Dodger's game.Alvarez acknowledges that in many ways gang culture is embedded in Latino culture in the city. But he says the vast majority of youth participate for social reasons and only stay in gangs an average of two years. The ringleaders — the so-called “five percenters” — average seven years and commit most of the anti-social acts and crimes associated with gangs. Alvarez believes restorative practices can reach both categories of gang member.

In addition to his work in schools, Alvarez has started an organization called Los Angeles Institute for Restorative Practices (LAIRP). The Institute does direct intervention in gang areas in the wake of violent incidents. They help families in need connect with resources, such as counseling and social services. They also conduct restorative conferences.

In one incident, a very active gang member shot and killed another man. The brother of the victim sought vengeance. Alvarez learned from talking with the killer that the killing was not gang-related and was unintended. Through restorative dialog, Alvarez managed to help the two men barter a truce. They would never be friends, he said, but they agreed to not perpetuate more killing over the incident.

Alvarez’s mission is ambitious — to transform systems of punishment and discipline into systems of healing and empowerment. He has also tapped into the growing scientific knowledge about the mind and emotions to inform his work. LAIPR specializes in training for law enforcement, detention centers and schools that have high populations of students at-risk. As an IIRP trainer, Alvarez has taught over 300 people to how conduct restorative conferences and has begun speaking at conferences, such as the upcoming IIRP World Conference in Detroit and a conference on sex-trafficking and school culture.

Almost all of the work Alvarez does in neighborhoods is voluntary. “I want to change lives by the things I do,” he says. “There’s so much work and it’s so exciting. We’re doing God’s work.”