Schools around the country are facing the need to integrate different kinds of programs aimed to improve school climate. A wide array of programs had been created, all with the goal of being more effective and humane than zero tolerance policies, which had proved ineffective at best. The many programs available, some with seemingly conflicting philosophies and methodologies, made it difficult for school administrators to choose the best way forward.

Schools around the country are facing the need to integrate different kinds of programs aimed to improve school climate. A wide array of programs had been created, all with the goal of being more effective and humane than zero tolerance policies, which had proved ineffective at best. The many programs available, some with seemingly conflicting philosophies and methodologies, made it difficult for school administrators to choose the best way forward.

In an effort to address this issue, in the summer of 2015, the International Institute for Restorative Practices (IIRP) Graduate School hosted an event in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA. The Integrating School Climate Reform Efforts Symposium brought together national leaders in restorative practices, Positive Behavior Interventions & Supports (PBIS), Social Emotional Learning (SEL) and bullying prevention, along with 150 educators from across North America.

As the convener of the Symposium, the IIRP instituted a fundamentally restorative process to bring together different voices and approaches to find common ground.

“The symposium brought people together to see how these different frames complement one another," comments IIRP Director of Continuing Education Keith Hickman. "At the Symposium, people committed to a process that is now resulting in more collaboration between evidence-based school climate programs, including joint research projects that will benefit schools.”

This is the first in a series of pieces that will look at various ways restorative practices and other approaches to improving school climate are compatible and can be integrated when implemented. This article draws on interviews conducted with Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP) director of training Jane Riese and PBIS researcher and trainer Jeffrey Sprague, Ph.D., who are currently leading a research and implementation project in rural Chesterfield County School District, South Carolina, that is integrating OBPP with PBIS. The research is being conducted by Clemson University and The University of Oregon, with funding from a National Institutes of Justice (NIJ) Safe Schools grant. A future article will examine how restorative practices and PBIS are currently being integrated in Jefferson County Public Schools, Louisville, Kentucky.

PBIS

PBIS began its development in the 1980s as a response to ideas, promoted by some behavioral researchers, that the most disruptive students could be made to change their behavior by extreme forms of punitive discipline, including being forced to hold extreme physical positions, accepting Tabasco poured in their mouths and even submitting to electric shocks. Academics at the University of Oregon, horrified by this trend, responded by cultivating the idea that educators should take a functional and values-driven approach by first discovering why students were behaving in disruptive ways and then providing positive behavior interventions and supports instead.

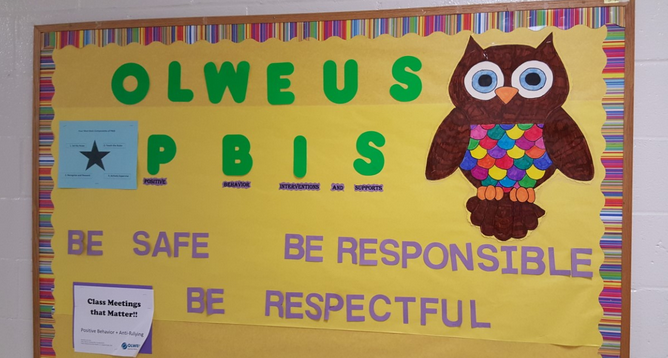

By the late 1990s, through the support of federal legislation and grants, PBIS developed into a school-wide approach to supplement the practices advocated for the most challenging students. Teachers inform all students in the school about behavior expectations for the classroom and also for the cafeteria, halls, buses and restrooms. They also provide students with instruction, in classes and assemblies, about how to live up to these standards. Further, they praise and reward students for good behavior.

“What we were trying to achieve early on was getting people to be safe, respectful and responsible,” says Dr. Sprague. “There were two sides to it. One was the promotion of positive behavior and fostering methods to recognize and reward students for doing the positive things. Another was the aim to reduce exclusionary discipline, such as office referrals and in- and out-of-school suspensions.”

Therefore, in addition to the school-wide efforts, PBIS developed ways to address the needs of students who otherwise might be sent out of class or given other kinds of more serious negative consequences. The model is based on a three-tiered system, depicted in the symbol of a pyramid, with general support for all students and more targeted and individualized types of support and intervention for those fewer students with higher needs.

PBIS practices respond in ways that deemphasize the role of punitive consequences with the goal of making “the student’s behaviors irrelevant, ineffective and inefficient,” says Dr. Sprague. “For example, if a student talks out to get attention, teach the student to seek attention more appropriately. By giving the student attention when he raises his hand and not when he calls out, you have made the problem behavior irrelevant and ineffective. If the new behavior works better for a student and he finds he can get attention more quickly, then the old behavior has become inefficient. This blearning takes time, and it is important to reinforce even small changes in behavior.”

OBPP

Like PBIS, OBPP was created in the 1980s as a whole-school approach to foster positive school climate. But it developed in response to an entirely different issue: bullying. The program was founded by pioneering researcher Dr. Dan Olweus to address bullying problems in rural Norway.

“The goal was to reduce existing bullying problems and prevent future ones from happening,” explains Riese. “Bullying really is a health crisis facing our world's youth. It has extreme consequences, and it affects kids across ethnicity, gender, grade, socioeconomic status and from urban, suburban and rural settings.”

On the proactive side, Olweus establishes school-wide behavioral expectations around the issue of bullying. Teachers implement class-level components primarily through the format of weekly student meetings or circles, similar to restorative practices. Through this instruction, administrators, teachers, staff, students and even parents learn how to prevent bullying and also report and respond to incidents of bullying when they do occur.

Historically, OBPP cautioned bringing together children who were doing the bullying with children who had been bullied. In recent years, the bullying prevention community, working with restorative practitioners, issued a White Paper, Integrating Bullying Prevention and Restorative Practices in Schools: Considerations for Practitioners and Policymakers (2014, The Center for Safe Schools, Clemson University’s Institute on Family and Neighborhood Life and the Highmark Foundation). The report explores whether and how restorative practices meetings may safely and judiciously be used to bring these parties together to address the issues of bullying.

Integration

In 2014, Riese and Dr. Sprague began working together to pilot the pairing of PBIS and OBPP implementation for the NIJ-funded research project. Shared components of the two programs support their dual implementation:

School-wide leadership team PBIS and Olweus each operate with an adult leadership team within the school building. In the pilot program, this includes a principal or assistant principal, representation from each grade, a school mental-health professional, such as a school counselor, a school social worker or a school psychologist, one or two parents and a non-teaching staff member. In the cases of a middle or high school, a student representative may also join the leadership team.

All staff receive training and support. “Everybody's involved,” says Riese. “It really takes the village, and everybody in the community needs to be on the same page, understanding the same concepts and providing the same messages to students.”

Parental involvement Parents in both programs are provided information and asked to reinforce the positive messages being conveyed by each program. Particularly in terms of bullying, the integrated program seeks to remove obstacles to parents feeling free to reach out to the school for information and to seek support.

Positive reinforcement Both programs support recognizing kind and respectful behavior. PBIS has more extensive protocols around bestowing praise, along with good behavior tickets and tokens. Dr. Sprague said he incorporated positive anti-bullying language into his direct training to the teams.

Addressing non-compliance and harm Both PBIS and OBPP emphasize calm, predictable and respectful responses to misbehavior, including bullying. Riese says, “Adult responses are designed to protect and support the bullied student, to correct and support better choices by the student who bullies and to appropriately address the behavior of the students who witness the bullying.” Dr. Sprague adds, “Much like the IIRP admonition to do things with instead of to students who misbehave or cause harm, PBIS strategies emphasize giving clear requests, choices and recognition for even small attempts to cooperate."

Data OBPP collects data annually on incidents of bullying. PBIS assembles reports on numbers, types and sources of discipline reports to seek patterns and make adjustments to the program. For the NIJ study, new tools are being developed to assess the fidelity of implementation of each program.

Explicit expectations, tools and guidelines “Our rules and values are posted and are taught," says Riese. Being very explicit in supporting, rewarding and encouraging students for doing the right thing is a key understanding of both these initiatives. We want to appreciate students who are being good citizens, as well as consequence students in a corrective and supportive, rather than a punitive way, when they need to learn to make better choices.”

Restorative elements

These common elements also parallel how the IIRP’s SaferSanerSchools Whole-School Change program is implemented school-wide through school-wide leadership teams, training of all staff, parental involvement, collection of data, explicit expectations and the implementation of proactive as well as responsive strategies to address behavior and school climate issues. This will be explored further in subsequent articles.

But for the purposes of this piece, it is interesting to emphasize the use of classroom circles in the PBIS/OBPP implementation in South Carolina as a way to foster conversation and engagement and build community.

In the study, teachers are using weekly classroom meetings to discuss how students might handle themselves in a wide range of contexts, such as peer pressure, friendships and dating violence. Riese, who has also been a restorative practitioner for more than 20 years, says that during this “circling up, students also get to know one another better, learn how to respect and care for one another and appreciate each other for who we are as different people. It’s something that translates so beautifully to restorative practices.”

Dr. Sprague adds that over the years, PBIS has also promoted a social learning approach through direct instruction. “Having conversations in a classroom circle about how we get along with each other really had great appeal to me. As I began to share the idea with school people, I also saw that as having great value for them, something that people would adopt.”

Conclusion

Efforts of this kind, informed by leaders in the field and verified through research will ease the effort for schools around the country to tailor these effective programs to meet their needs.

“That can be overwhelming to administration as well as teachers,” says Riese. “I think the work that we're doing on the integration at the front end feels a little less overwhelming. We're braiding this together for you in ways that we, as program people, feel are a perfect fit.”