News & Announcements

- Details

- Written by American Humane

A special double volume (PDF) of "Protecting Children", the journal of the American Humane Association''s National Center on Family Group Decision Making. This volume contains reports on FGDM research from around the world and offers "considerable support for the advancement of FGDM and good reasons to explore ways to mainstream its practice."

- Details

- Written by John Blad

John Blad, of Erasmus University Rotterdam, Netherlands, chief editor of the Dutch Journal for Restorative Justice, discusses the Dutch government''s shift from having one of the most lenient penal climates in the world to one that is much more punitive. He attributes the rise in his country''s incarceration and violent crime rates to the new policies and argues for implementation of restorative justice instead. The paper was presented at the first in a series of three IIRP conferences with the theme, "Building a Global Alliance for Restorative Practices and Family Empowerment," in Veldhoven, Netherlands, August 28-30, 2003.

- Details

- Written by Jim Boyack, Helen Bowen

Helen Bowen and Jim Boyack, trustees of the Restorative Justice Trust of Auckland, New Zealand, discuss developments in adult restorative justice initiatives in their country, where youth offender family group conferences (FGCs) have been legally mandated since 1989. The 2002 Sentencing, Parole, and Victims''Rights acts have made New Zealand the world''s first country to provide for restorative justice practices and principles at all stages of the criminal justice process. The paper was presented at the first in a series of three IIRP conferences with the theme, "Building a Global Alliance for Restorative Practices and Family Empowerment," in Veldhoven, Netherlands, August 28-30, 2003.

- Details

- Written by Graham Waite

Graham Waite, superintendent, Northern Territory Police, Australia, discusses the Territory''s pre-court juvenile diversion scheme, which provides alternatives, such as Real Justice conferencing, to prosecution and sentencing of young offenders (including Aboriginal youth), in the formal justice system. The scheme produced significant decreases in reoffending and high satisfaction levels. The paper was presented at the first in a series of three IIRP conferences with the theme, "Building a Global Alliance for Restorative Practices and Family Empowerment," in Veldhoven, Netherlands, August 28-30, 2003.

- Details

- Written by Roel van Pagée, Joke Henskens-Reijman

Joke Henskens-Reijman and Roel van Pagée, principals, Terra College, The Hague, Netherlands, speak of their encouraging experiences implementing restorative practices in two large, urban secondary schools where the ethnic make up has recently changed from a homogeneous Dutch population to one that includes children from multiple ethnic and national backgrounds. The paper was presented at the first in a series of three IIRP conferences with the theme, "Building a Global Alliance for Restorative Practices and Family Empowerment," in Veldhoven, Netherlands, August 28-30, 2003.

- Details

- Written by Karin Gunderson

Karin Gunderson, of the Northwest Institute for Children and Families, University of Washington School of Social Work, Seattle, Washington, U.S.A, reports the positive results of two significant studies on family group conferencing (FGC): "Long Term and Immediate Outcomes of Family Group Conferencing in Washington State," June 2000, and "''Connected and Cared for'': Family Group Conferencing for Youth in Care," June 2002. The paper was presented at the first in a series of three IIRP conferences with the theme, "Building a Global Alliance for Restorative Practices and Family Empowerment," in Veldhoven, Netherlands, August 28-30, 2003.

- Details

- Written by Lode Walgrave

Lode Walgrave, of Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium, speaks about the Belgian juvenile justice initiative, which has addressed serious juvenile offenses, including arson, carjacking, armed robbery, serious physical violence and aggravated theft, using the New Zealand model of family group conferencing (FGC), with cases referred by youth court judges. The paper was presented at the first in a series of three IIRP conferences with the theme, "Building a Global Alliance for Restorative Practices and Family Empowerment," in Veldhoven, Netherlands, August 28-30, 2003.

- Details

- Written by Paul McCold, Ted Wachtel

This paper by Paul McCold and Ted Wachtel presents a concise summary of the restorative justice theory that the IIRP has promulgated over the last several years. The theory provides the framework for a comprehensive answer to the how, what and who of the restorative justice paradigm. The paper was presented by Paul McCold at the XIII World Congress of Criminology, August 10-15, 2003, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Also available in Portuguese and Spanish languages.

- Details

- Written by Paul McCold

Paper presented at the XIII World Congress of Criminology,

10-15 August 2003, Rio de Janeiro.

Restorative justice is a new way of looking at criminal justice that focuses on repairing the harm done to people and relationships rather than on punishing offenders. Originating in the 1970s as mediation between victims and offenders, in the 1990s restorative justice broadened to include communities of care as well, with victims’ and offenders’ families and friends participating in collaborative processes called “conferences” and “circles.” This new focus on healing and the related empowerment of those affected by a crime seems to have great potential for enhancing social cohesion in our increasingly disconnected societies. Restorative justice and its emerging practices constitute a promising new area of study for social science.

In this paper, we propose a conceptual theory of restorative justice so that social scientists may test these theoretical concepts and their validity in explaining and predicting the effects of restorative justice practices. The foundational postulate of restorative justice is that crime harms people and relationships and that justice requires the healing of the harm as much as possible. Out of this basic premise arise key questions: who is harmed, what are their needs and how can those needs be met?

A CONCEPTUAL THEORY OF RESTORATIVE JUSTICE

Restorative justice is a collaborative process involving those most directly affected by a crime, called the “primary stakeholders,” in determining how best to repair the harm caused by the offense. But who are the primary stakeholders in restorative justice and how shall they be involved in the search for justice? Our proposed theory of restorative justice has three distinct but related conceptual structures: the Social Discipline Window (Wachtel, 1997, 2000; Wachtel & McCold, 2000), Stakeholder Roles (McCold, 1996, 2000) and the Restorative Practices Typology (McCold, 2000; McCold & Wachtel, 2002). Each of these, in turn, explains the how, what and who of restorative justice theory.

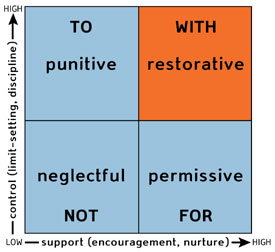

Social Discipline Window

|

|

Figure 1. Social Discipline Window

|

Everyone with an authority role in society faces choices in deciding how to maintain social discipline: parents raising children, teachers in classrooms, employers supervising employees or justice professionals responding to criminal offences. Until recently, Western societies have relied on punishment, usually perceived as the only effective way to discipline those who misbehave or commit crimes.

Punishment and other choices are illustrated by the Social Discipline Window (Figure 1), which is created by combining two continuums: “control,” exercising restraint or directing influence over others, and “support,” nurturing, encouraging or assisting others. For simplicity, the combinations from each of the two continuums are limited to “high” and “low.” Clear limit-setting and diligent enforcement of behavioral standards characterize high social control. Vague or weak behavioral standards and lax or nonexistent regulation of behavior characterize low social control. Active assistance and concern for well-being characterize high social support. Lack of encouragement and minimal provision for physical and emotional needs characterize low social support. By combining a high or low level of control with a high or low level of support the Social Discipline Window defines four approaches to the regulation of behavior: punitive, permissive, neglectful and restorative.

The punitive approach, with high control and low support, is also called “retributive.” It tends to stigmatize people, indelibly marking them with a negative label. The permissive approach, with low control and high support, is also called “rehabilitative” and tends to protect people from experiencing the consequences of their wrongdoing. Low control and low support are simply neglectful, an approach characterized by indifference and passivity.

The restorative approach, with high control and high support, confronts and disapproves of wrongdoing while affirming the intrinsic worth of the offender. The essence of restorative justice is collaborative problem-solving. Restorative practices provide an opportunity for those who have been most affected by an incident to come together to share their feelings, describe how they were affected and develop a plan to repair the harm done or prevent a reoccurrence. The restorative approach is reintegrative, allowing the offender to make amends and shed the offender label.

Four words serve as a shorthand to distinguish the four approaches: NOT, FOR, TO and WITH. If neglectful, one would NOT do anything in response to offending behavior. If permissive, one would do everything FOR the offender, asking little in return and often making excuses for the wrongdoing. If punitive, one would respond by doing things TO the offender, admonishing and punishing, but asking little thoughtful or active involvement of the offender. If restorative, one engages WITH the offender and others, encouraging active and thoughtful involvement from the offender and inviting all others affected by the offense to participate directly in the process of healing and accountability. Cooperative engagement is a critical element of restorative justice.

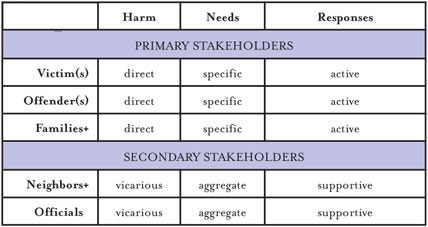

Stakeholder Roles

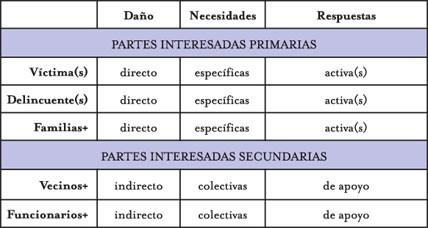

|

|

Figure 2. Stakeholder Roles

|

The second structure of our theory of restorative justice, the Stakeholder Roles (Figure 2), relates the harm caused by the offense to the specific needs of each stakeholder created by that offense, and to the restorative responses required to meet those needs. This causal structure distinguishes the interests of the primary stakeholders—those most affected by a specific offense—from those indirectly affected.

The primary stakeholders are, principally, the victims and offenders, because they are the most directly affected. But those who have a significant emotional connection with a victim or offender, such as parents, spouses, siblings, friends, teachers or co-workers, are also directly affected. They constitute the victims’ and offenders’ communities of care. The harm done, needs created and the restorative responses of primary stakeholders are specific to the particular offense and require active participation to achieve the greatest healing.

The secondary stakeholders include those who live nearby or those who belong to educational, religious, social or business organizations whose area of responsibility or participation includes the place or people affected by the incident. The whole of society, as represented by government officials, is also a secondary stakeholder. The harm to both sets of secondary stakeholders is vicarious and impersonal; their needs are aggregate, not specific, and their most restorative response is to support restorative processes in general.

All primary stakeholders need an opportunity to express their feelings and have a say in how to repair the harm. Victims are harmed by the loss of control they experience as a result of the offense. They need to regain a sense of personal power. This empowerment is what transforms victims into survivors. Offenders damage their relationships with their own communities of care by betraying trust. To regain that trust, they need to be empowered to take responsibility for their wrongdoing. Their communities of care meet their needs by ensuring that something is done about the incident, that its wrongfulness is acknowledged, that constructive steps are taken to prevent further offending and that victims and offenders are reintegrated into their respective communities.

The secondary stakeholders, those who are not emotionally connected to the specific victims and offenders, must not steal the conflict from those to whom it belongs by interfering with the opportunity for healing and reconciliation. The most restorative response for the secondary stakeholders is to support and facilitate processes in which the primary stakeholders determine for themselves the outcome of the case. Such processes will reintegrate both victims and offenders and simultaneously strengthen civil society by enhancing social cohesion and empowering and improving the citizenry’s ability to solve its own problems.

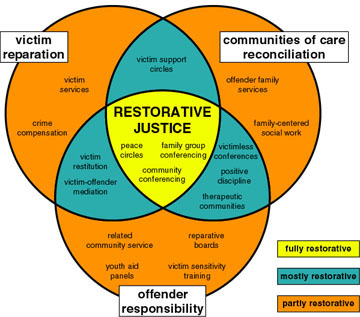

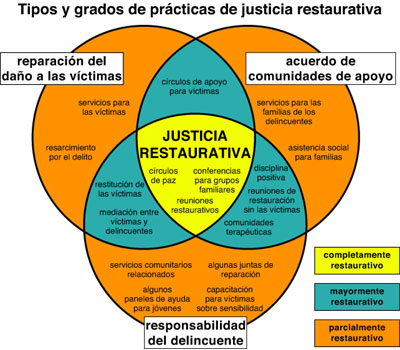

Restorative Practices Typology

|

|

Figure 3. Restorative Practices Typology

|

Restorative justice is a process involving the primary stakeholders in determining how best to repair the harm done by an offense. The three primary stakeholders in restorative justice are victims, offenders and their communities of care, whose needs are, respectively, getting reparation, taking responsibility and achieving reconciliation. The degree to which all three are involved in meaningful emotional exchange and decision-making is the degree to which any form of social discipline can be termed fully “restorative.” These three sets of primary stakeholders are represented by the three overlapping circles in Figure 3. The very process of interacting is critical to meeting stakeholders’ emotional needs. The emotional exchange necessary for meeting the needs of all those directly affected cannot occur with only one set of stakeholders participating. The most restorative processes involve the active participation of all three sets of primary stakeholders.

When criminal justice practices involve only one group of primary stakeholders, as in the case of governmental financial compensation for victims, the process can only be called “partly restorative.” When a process such as victim-offender mediation includes two principal stakeholders but excludes their communities of care, the process is “mostly restorative.” Only when all three sets of primary stakeholders are actively involved, such as in conferences or circles, is a process “fully restorative.”

CONCLUSION

Crimes harm people and relationships. Justice requires that harm be repaired as much as possible. Restorative justice is not done because it is deserved, but because it is needed. Restorative justice is ideally achieved through a cooperative process involving all the primary stakeholders in determining how best to repair the harm done by the offense.

The conceptual theory presented here provides the framework for a comprehensive answer to the how, what and who of the restorative justice paradigm. The Social Discipline Window describes how conflict can be transformed into cooperation. The Stakeholder Roles structure demonstrates that repair of the emotional and relational harm necessitates the empowerment of the primary stakeholders, those most directly affected. The Restorative Practices Typology demonstrates why participation of the victims, offenders and their communities of care are all required to repair the harm caused by the criminal act.

A criminal justice system that merely doles out punishment to offenders and sidelines victims does not address the emotional or relational needs of those who have been affected by crime. In a world where people feel increasingly alienated, restorative justice restores and builds positive feelings and relationships. A restorative criminal justice system aims not just to reduce crime, but to reduce the impact of crime as well. The capacity of restorative justice to address these emotional and relational needs and engage the citizenry in doing so is the key to achieving and sustaining a healthy civil society.

REFERENCES

McCold, P. (1996). Restorative justice and the role of community. In B. Galaway & J. Hudson (Eds.), Restorative Justice: International Perspectives (pp. 85-102). Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press.

McCold, P. (2000). Toward a mid-range theory of restorative criminal justice: A reply to the Maximalist model. Contemporary Justice Review, 3(4), 357-414.

McCold, P., & Wachtel, T. (2002). Restorative justice theory validation. In E. Weitekamp and H-J. Kerner (Eds.), Restorative Justice: Theoretical Foundations (pp. 110-142). Devon, UK: Willan Publishing.

Wachtel, T. (1997). Real Justice: How to Revolutionize our Response to Wrongdoing. Pipersville, PA: Piper’s Press.

Wachtel, T. (2000). Restorative practices with high-risk youth. In G. Burford & J. Hudson (Eds.), Family Group Conferencing: New Directions in Community Centered Child & Family Practice (pp. 86-92). Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

Wachtel, T., & McCold, P. (2000). Restorative justice in everyday life. In J. Braithwaite and H. Strang (Eds.), Restorative Justice in Civil Society (pp. 117-125). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Details

- Written by Paul McCold

Ponencia presentada en el XIII Congreso Mundial sobre Criminología,

del 10 al 15 de agosto de 2003, en Rîo de Janeiro.

La justicia restaurativa es una nueva manera de considerar a la justicia penal la cual se concentra en reparar el daño causado a las personas y a las relaciones más que en castigar a los delincuentes. La justicia restaurativa surgió en la década de los años 70 como una forma de mediación entre víctimas y delincuentes y en la década de los años 90 amplió su alcance para incluir también a las comunidades de apoyo, con la participación de familiares y amigos de las víctimas y los delincuentes en procedimientos de colaboración denominados “reuniones de restauración” y “círculos.” Este nuevo enfoque en el proceso de subsanación para las personas afectadas por un delito y la obtención de control personal asociado parece tener un gran potencial para optimizar la cohesión social en nuestras sociedades cada vez más indiferentes. La justicia restaurativa y sus prácticas emergentes constituyen una nueva y promisoria área de estudio para las ciencias sociales.

En la presente ponencia, proponemos una teoría conceptual sobre la justicia restaurativa para que los científicos sociales puedan evaluar estos conceptos teóricos y su validez para explicar y predecir los resultados de las prácticas de justicia restaurativa. El postulado fundamental de la justicia restaurativa es que el delito perjudica a las personas y las relaciones y que la justicia necesita la mayor subsanación del daño posible. De esta premisa básica surgen preguntas clave: ¿quién es el perjudicado, cuáles son sus necesidades y cómo se pueden satisfacer dichas necesidades?

UNA TEORÍA CONCEPTUAL SOBRE JUSTICIA RESTAURATIVA

La justicia restaurativa es un proceso de colaboración que involucra a las “partes interesadas primarias,” es decir, a las personas afectadas de forma más directa por un delito, en la determinación de la mejor manera de reparar el daño causado por el delito. Pero, ¿quiénes son las partes interesadas primarias en la justicia restaurativa y cómo deben participar en la búsqueda de la justicia? La teoría de justicia restaurativa que proponemos cuenta con tres estructuras conceptuales distintas pero relacionadas: la Ventana de la disciplina social (Wachtel 1997, 2000; Wachtel & McCold 2000), la Función de las partes interesadas (McCold 1996, 2000), y la Tipología de las prácticas restaurativas (McCold 2000; McCold & Wachtel, 2002). Cada una de ellas, a su vez, explica el cómo, qué y quién de la teoría de justicia restaurativa.

Ventana de la disciplina social

|

|

Figura 1. Ventana de la disciplina social

|

Toda persona en la sociedad con un papel que suponga autoridad enfrenta opciones al decidir cómo mantener la disciplina social: los padres que educan a sus hijos, los maestros en las aulas, los empleadores que supervisan a los empleados o los profesionales de la justicia que actúan ante los delitos. Hasta hace poco las sociedades occidentales se basaban en el castigo, generalmente percibido como la única manera eficaz de disciplinar a aquellas personas que proceden mal o cometen un delito.

El castigo y otras opciones están ilustrados en la Ventana de la disciplina social (Figura 1), la cual se genera mediante la combinación de dos secuencias: “control,” imponer limitaciones o ejercer influencia sobre otros, y “apoyo,” enseñar, estimular o asistir a otros. Por razones de simplicidad, las combinaciones de cada una de las dos secuencias se limitan a “alto” y “bajo.” Un control social alto se caracteriza por la imposición de límites bien definidos y el pronto cumplimiento de los principios conductuales. Un control social bajo se caracteriza por principios conductuales imprecisos o débiles y normas de conducta poco estrictas o inexistentes. Un apoyo social alto se caracteriza por la asistencia activa y el interés por el bienestar. Un apoyo social bajo se caracteriza por la falta de estímulo y la mínima consideración por las necesidades físicas y emocionales. Mediante la combinación de un nivel alto o bajo de control con un nivel alto o bajo de apoyo la Ventana de la disciplina social define cuatro enfoques para la reglamentación de la conducta: punitivo, permisivo, negligente y restaurativo.

El enfoque punitivo, con control alto y apoyo bajo, se denomina también “retributivo.” Tiende a estigmatizar a las personas, marcándolas indeleblemente con una etiqueta negativa. El enfoque permisivo, con control bajo y apoyo alto, se denomina también “rehabilitativo” y tiende a proteger a las personas para que no sufran las consecuencias de sus delitos. Un control bajo y un apoyo bajo son simplemente negligentes, un enfoque caracterizado por la indeferencia y la pasividad.

El enfoque restaurativo, con control alto y apoyo alto, confronta y desaprueba los delitos al tiempo que ratifica el valor intrínseco de los delincuentes. La esencia de la justicia restaurativa es la resolución de problemas de manera colaboradora. Las prácticas restaurativas brindan una oportunidad para que aquellas personas que se hayan visto más afectadas por un incidente se reúnan para compartir sus sentimientos, describir cómo se han visto afectadas y desarrollar un plan para reparar el daño causado o evitar que ocurra nuevamente. El enfoque restaurativo es reintegrativo y permite que el delincuente se rectifique y se quite la etiqueta de delincuente.

Cuatro palabras sirven como referencia para distinguir los cuatro enfoques: NO, POR, AL y CON. Si el enfoque es negligente, NO se hará nada en respuesta a la conducta delictiva. Si es permisivo, se hará todo POR el delincuente, pidiendo poco a cambio y a menudo tratando de justificar el delito. Si es punitivo, se responderá haciéndole algo AL delincuente, amonestándolo y castigándolo, pero esperando poca participación reflexiva o activa por parte del delincuente. Si es restaurativo, se comprometerá CON el delincuente y otras personas, fomentando una participación activa y reflexiva por parte del delincuente e invitando a todas aquellas personas afectadas por el delito a participar directamente en el proceso de subsanación y de aceptación de responsabilidad. El compromiso cooperativo es un elemento fundamental de la justicia restaurativa.

Función de las partes interesadas.

|

|

Figura 2. Función de las partes interesadas

|

La segunda estructura de nuestra teoría de justicia restaurativa, las Funciones de las partes interesadas (Figura 2), relaciona el daño ocasionado por el delito con las necesidades específicas de cada parte interesada que surgieron a partir de dicho delito y con las respuestas restaurativas necesarias para satisfacer dichas necesidades. Esta estructura causal diferencia los intereses de las partes interesadas primarias -aquellas personas más afectadas por un delito específico- de los de las personas indirectamente afectadas.

Las partes interesadas primarias son, principalmente, las víctimas y los delincuentes puesto que son las partes más afectadas directamente. Pero aquellos que tienen una conexión afectiva importante con la víctima o el delincuente, como por ejemplo, padres, cónyuges, hermanos, amigos, maestros o compañeros de trabajo, también se ven directamente afectados. Ellos constituyen las comunidades de apoyo de las víctimas y los delincuentes. El daño ocasionado, las necesidades creadas y las respuestas restaurativas de las partes interesadas primarias son específicas del delito en particular y exigen una participación activa para lograr el mayor nivel de subsanación.

Las partes interesadas secundarias incluyen a aquellas personas que viven cerca o a aquellas que pertenecen a organizaciones educativas, religiosas, sociales o comerciales cuya área de responsabilidad o participación abarca el lugar o las personas afectadas por el incidente. Toda la sociedad, representada por funcionarios del gobierno, constituye también una parte interesada secundaria. El daño causado a ambos grupos de partes interesadas secundarias es indirecto e impersonal, sus necesidades son colectivas e inespecíficas, y su mayor respuesta restaurativa es apoyar los procedimientos restaurativos en general.

Todas las partes interesadas primarias necesitan una oportunidad para expresar sus sentimientos y participar en la decisión sobre la manera de reparar el daño. Las víctimas se ven perjudicadas por la pérdida de control que sufren como consecuencia del delito. Necesitan recuperar un sentido de dominio personal. Esta obtención de control personal es lo que transforma a las víctimas en sobrevivientes. Los delincuentes dañan sus relaciones con sus propias comunidades de apoyo traicionando la confianza. Para recobrar esa confianza, necesitan obtener control personal para asumir la responsabilidad por el delito cometido. Sus comunidades de apoyo satisfacen sus necesidades asegurando que se haga algo con respecto al incidente, que se reconozca su carácter erróneo, que se tomen medidas constructivas para evitar que ocurran otros delitos y que las víctimas y los delincuentes se reintegren en sus respectivas comunidades.

Las partes interesadas secundarias, aquellas personas que no se encuentran emocionalmente vinculadas a las víctimas o los delincuentes específicos, no deben despojar del conflicto a aquellos a quienes les pertenece interfiriendo en la oportunidad de subsanación y reconciliación. La respuesta más restaurativa para las partes interesadas secundarias es apoyar y facilitar los procedimientos en los que las partes interesadas primarias deciden por ellas mismas el resultado del caso. Dichos procedimientos reinsertarán a las víctimas y los delincuentes y al mismo tiempo fortalecerán a la sociedad civil mediante la optimización de la cohesión social y la obtención de control personal y mejoramiento de la capacidad de los ciudadanos para resolver sus propios problemas.

Tipología de las prácticas restaurativas

|

|

Figura 3. Tipología de las prácticas restaurativas

|

La justicia restaurativa es un proceso que involucra a las partes interesadas primarias en la decisión sobre la mejor manera de reparar el daño ocasionado por un delito. Las tres partes interesadas primarias en la justicia restaurativa son las víctimas, los delincuentes y sus comunidades de apoyo, cuyas necesidades son, respectivamente, lograr la reparación del daño, asumir la responsabilidad y llegar a un acuerdo. El grado en que las tres partes participan en intercambios emocionales significativos y la toma de decisiones es el grado según el cual toda forma de disciplina social puede ser calificada como completamente “restaurativa.” Estos tres grupos de partes interesadas primarias están representados por tres círculos superpuestos en la Figura 3. El propio proceso de interacción es fundamental para satisfacer las necesidades emocionales de las partes interesadas. El intercambio emocional necesario para satisfacer las necesidades de todas aquellas personas directamente afectadas no puede tener lugar con la participación de un solo grupo de partes interesadas. Los procesos más restaurativos incluyen la participación activa de los tres grupos de partes interesadas primarias.

Cuando las prácticas de la justicia penal incluyen sólo a un grupo de partes interesadas primarias, como en el caso del resarcimiento económico para las víctimas por parte del gobierno, el proceso sólo se puede llamar “parcialmente restaurativo.” Cuando un procedimiento como el de mediación entre víctimas y delincuentes incluye dos partes interesadas principales pero excluye a las comunidades de apoyo, el proceso es “mayormente restaurativo.” El proceso es “completamente restaurativo” sólo cuando los tres grupos de partes interesadas primarias participan activamente, como por ejemplo en reuniones de restauración o círculos.

CONCLUSIÓN

Los delitos dañan a las personas y las relaciones. La justicia exige que el daño se repare tanto como sea posible. La justicia restaurativa no se aplica porque es merecida, sino porque es necesaria. La justicia restaurativa se logra de manera ideal mediante un proceso cooperativo que involucra a todas las partes interesadas primarias en la decisión sobre la mejor manera de reparar el daño ocasionado por el delito.

La teoría conceptual aquí presentada proporciona el marco para una respuesta global al cómo, qué y quién del paradigma de justicia restaurativa. La Ventana de la disciplina social describe la manera en que el conflicto se puede transformar en colaboración. La estructura de las Funciones de las partes interesadas demuestra que la reparación del daño emocional y relacional requiere la obtención de control personal de las partes interesadas primarias, aquellas personas afectadas de forma más directa. La Tipología de las prácticas restaurativas demuestra el motivo por el cual la participación de las víctimas, los delincuentes y sus comunidades de apoyo es necesaria para reparar el daño causado por el acto delictivo.

Un sistema de justicia penal que solamente imparte castigos a los delincuentes y excluye a las víctimas no encara las necesidades emocionales y relacionales de aquellas personas que se vieron afectadas por el delito. En un mundo donde las personas se sienten cada vez más alienadas, la justicia restaurativa restablece y desarrolla sentimientos y relaciones positivos. Un sistema restaurativo de justicia penal apunta no sólo a reducir la cantidad de delitos, sino también a disminuir el impacto de los mismos. La capacidad de la justicia restaurativa de tratar estas necesidades emocionales y relacionales y de comprometer a los ciudadanos en el proceso es la clave para lograr y mantener una sociedad civil sana.

REFERENCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

McCold, P. (1996). Restorative justice and the role of community [La justicia restaurativa y la función de la comunidad]. En B. Galaway & J. Hudson (Eds.) Restorative Justice: International Perspectives (pp. 85-102). Monsey, NY: Criminal Justice Press.

McCold, P. (2000). Toward a mid-range theory of restorative criminal justice: A reply to the Maximalist model [Hacia una teoría de justicia restaurativa penal de alcance intermedio: Una respuesta al modelo Maximalista]. Contemporary Justice Review, 3(4), 357-414.

McCold, P., & Wachtel, T. (2002). Restorative justice theory validation [Validación de la teoría de justicia restaurativa]. En E. Weitekamp and H-J. Kerner (Eds.), Restorative Justice: Theoretical Foundations (pp. 110-142). Devon, UK: Willan Publishing.

Wachtel, T. (1997). Real Justice: How to Revolutionize our Response to Wrongdoing [La justicia verdadera: Cómo cambiar radicalmente nuestra respuesta ante los delitos]. Pipersville, PA: Piper’s Press.

Wachtel. T. (2000). Restorative practices with high-risk youth [Prácticas restaurativas con jóvenes de alto riesgo]. En G. Burford & J. Hudson (Eds.). Family Group Conferencing: New Directions in Community Centered Child & Family Practice (pp. 86-92). Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

Wachtel, T., & McCold, P. (2000). Restorative justice in everyday life [La justicia restaurativa en la vida diaria]. En J. Braithwaite and H. Strang (Eds.), Restorative Justice in Civil Society (pp. 117-125). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Restorative Works Year in Review 2023 (PDF)

All our donors are acknowledged annually in Restorative Works.