News & Announcements

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

St. Croix Valley Restorative Justice Program (SCVRJP), based in River Falls, Wisconsin, USA, has developed a unique practice for working with young adults who have been arrested for crimes such as underage drinking, possession of drugs and paraphernalia, disorderly conduct and teen driving offenses. Using a restorative circle process, SCVRJP brings together offenders referred by the local courts, universities and high schools, who meet together with previous offenders and other community volunteers who have been impacted by these issues. A volunteer circle-keeper facilitates a focused discussion to present information to participants and to share a variety of perspectives.

The process builds upon victim impact panels (VIP), a process in which victims and family of drunk driving accidents tell their stories to those caught drinking and driving. Often VIPs take place in a hall full of participants, with the victims telling their stories from a podium or stage. Kris Miner, director of SCVRJP since 2004, wanted to make the experience more intimate and meaningful. “We continued to call them panels at first,” she said, “but actually we ran them as restorative justice circles.”

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

The Latin American Institute of Restorative Practices (El Instituto Latino Americano de Prácticas Restaurativas or ILAPR), IIRP’s affiliate based in Lima, Peru, has been working for three years to foster the development of restorative practices throughout South America and in Mexico. Jean Schmitz, director of ILAPR, and his colleagues, have provided basic restorative practices training to approximately 1,000 people in seven countries, including Peru, Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador and Columbia. This professional development is beginning to have an impact in the fields of education and criminal justice.

The Latin American Institute of Restorative Practices (El Instituto Latino Americano de Prácticas Restaurativas or ILAPR), IIRP’s affiliate based in Lima, Peru, has been working for three years to foster the development of restorative practices throughout South America and in Mexico. Jean Schmitz, director of ILAPR, and his colleagues, have provided basic restorative practices training to approximately 1,000 people in seven countries, including Peru, Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, Bolivia, Ecuador and Columbia. This professional development is beginning to have an impact in the fields of education and criminal justice.

In Lima, the capital of Peru, Schmitz trained a team of 30 professionals who work with adult and youth offenders in non-punitive alternative justice programs, such as those that assign community service work. Prior to the training, said Schmitz, the professionals were interested in only one thing: whether the offenders were completing their required service. Now, with restorative practices as a theoretical and practical foundation, the professionals have begun to employ circles with the offenders. In addition to the community service work, they give offenders a chance to talk to one another using a circle format, reflecting on their actions and discussing how they might repair the harm they’ve caused. During one circle Schmitz attended, he was impressed by one of the offenders, who talked about how important it was for him to learn about the experience of others in the group. The offender said he is more conscious of his own actions now. He said he believes he has righted his wrongs and no longer owes a debt to those he harmed.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

In this short video segment, Les Davey, chief executive of IIRP Europe, discusses work his organization has done in Ireland with victims of sexual abuse by clergy. Sexual abuse cases require careful handling, but they can be powerful experiences, especially for victims. In this video Davey describes one example of the positive effects a conference had for a victim of abuse, who was finally able to sleep well after the restorative meeting. Davey has recently been approached to run a restorative conference for a child in England who was abused in her home at a young age by an ex-boyfriend of her mother.

Watch the short video, "Restorative responses to sexual abuse by clergy," at youtube.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

Schools

• California’s Fix School Discipline, a project of Public Counsel, encourages schools in California to address school climate in their newly required Local Control Accountability Plans (LCAP). In a recent blog post counting down to the July 1 deadline, they praise Fresno schools:

• California’s Fix School Discipline, a project of Public Counsel, encourages schools in California to address school climate in their newly required Local Control Accountability Plans (LCAP). In a recent blog post counting down to the July 1 deadline, they praise Fresno schools:

Restorative Practices, the critical alternative to suspension in Fresno, is used to build a sense of school community and resolve conflict by repairing harm and restoring positive relationships through the use of regular ‘restorative circles’ where students and educators work together to set academic goals, develop core values for the classroom community and resolve conflicts.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

In "Restoring Relationships: What churches can learn from restorative justice," Paul Pastor for Christianity Today writes:

In "Restoring Relationships: What churches can learn from restorative justice," Paul Pastor for Christianity Today writes:

Bruce Schenk is a Lutheran pastor and the director of Canada's International Institute for Restorative Practices. The IIRP is an internationally affiliated organization dedicated to education and research in restorative justice — an approach to community conflict that emphasizes relationships. Bruce has worked in the area for the past 15 years, using his skills in contexts ranging from incarcerated juvenile offenders to church congregational decisions. Now, he's bringing what he's learned to a wider audience. His trainings have been sponsored by the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Canada to better equip clergy and laity to foster healthy relationships and manage conflict.

I asked Tom Albright of Ripple Church in Allentown, Pennsylvania how Schenk's philosophy has impacted his congregation. "Shalom and reconciliation are the heart of the gospel," Albright said. "Restorative practices give us the tools to enact peace, redemption, reconciliation, and healthy relationships." Ripple's pastoral staff are all trained in restorative practices—a story for another day, but one worth telling.

Schenk and I sat down for a phone conversation on restorative justice in church settings. He thinks Christian leaders need to rethink decision-making—and conflict—in their congregations, and why "thinking restoratively" is at the heart of the gospel.

Read Restoring Relationships: What churches can learn from restorative justice.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

Cody Gates and his father, Gordy Gates, discuss the impact of a restorative conference after Cody set off fireworks into a crowd, from a video presentation sponsored by Easter Seals / Goodwill of the Northwest (watch below).There’s a restorative revolution taking place across the U.S. state of Idaho, originating in the field of juvenile justice and radiating out to schools and communities. It began a few years ago and is being driven by a mostly rural eight-county district in south central Idaho.

Cody Gates and his father, Gordy Gates, discuss the impact of a restorative conference after Cody set off fireworks into a crowd, from a video presentation sponsored by Easter Seals / Goodwill of the Northwest (watch below).There’s a restorative revolution taking place across the U.S. state of Idaho, originating in the field of juvenile justice and radiating out to schools and communities. It began a few years ago and is being driven by a mostly rural eight-county district in south central Idaho.

Judge Mark Ingram, a magistrate court judge for the Fifth Judicial District in Idaho, was exposed to restorative practices while practicing law 12 years ago. He worked with various kinds of mediation, beginning with personal injury but leaning more toward child custody and victim-offender mediation because they were “more relational,” he said. When he became a judge in his hometown of Shoshone, the Lincoln County seat, with a population of about 1,500, he began to look for ways to help resolve tensions in the community between old-time farmers and new transplants. A Community Justice Coalition with a restorative mission organized large community meetings to foster helpful discussions. But Ingram continued to struggle with the question of how to bring a restorative spirit into the court system in a practical way.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

Restorative practices is about helping people have the "right conversation" so they can work through conflict and build relationships, says restorative practices pioneer Terry O'Connell, director of Real Justice Australia (iirp.edu/au).

In the first part of this short video, he talks about his work with young students who learn in school how to frame that conversation, even when they go home and have problems with their friends.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

Father Chris Riley, Founder and CEO of Youth Off the Streets: "Restorative practices are focused on healing the community rather than retribution and blame and our troubled kids need this to be the focus."Youth Off the Streets (YOTS), a large youth-serving agency located in and around Sydney, Australia, has been on a journey of utilizing restorative justice to respond to misbehavior and has recently expanded that to implementing restorative practices to build community and relationships. The organization runs a variety of community, educational, residential and rehabilitation programs for at-risk and adjudicated youth.

Father Chris Riley, Founder and CEO of Youth Off the Streets: "Restorative practices are focused on healing the community rather than retribution and blame and our troubled kids need this to be the focus."Youth Off the Streets (YOTS), a large youth-serving agency located in and around Sydney, Australia, has been on a journey of utilizing restorative justice to respond to misbehavior and has recently expanded that to implementing restorative practices to build community and relationships. The organization runs a variety of community, educational, residential and rehabilitation programs for at-risk and adjudicated youth.

YOTS Founder and CEO Father Chris Riley said, “Several years ago, a young teacher approached me about looking for strategies to deal with troubled students, and I recommended she look at restorative justice. She embraced this literature, and all of our schools now operate using the RJ material.”

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

Faith Communities

“Restoring Relationships: What churches can learn from restorative justice” – Christianity Today's Paul Pastor presents a lengthy interview with Bruce Schenk, director of IIRP Canada.

IIRP news

Dóra Szegő, IIRP Europe's new Assistant Director for Central and Eastern Europe• IIRP Europe welcomes Dóra Szegő as Assistant Director for Central and Eastern Europe.

Dóra Szegő, IIRP Europe's new Assistant Director for Central and Eastern Europe• IIRP Europe welcomes Dóra Szegő as Assistant Director for Central and Eastern Europe.

• Call for Presenters: Offer a session at IIRP's 17th World Conference.

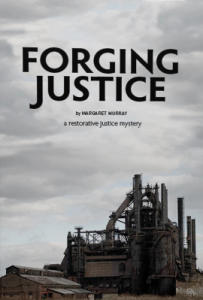

• Martin Wright reviews Margaret Murray's Forging Justice: A Restorative Justice Mystery.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

Forging justice: A restorative justice mystery. Margaret Murray. Pipersville, PA: Piper's Press, 2013. 231 pp.

Forging justice: A restorative justice mystery. Margaret Murray. Pipersville, PA: Piper's Press, 2013. 231 pp.

ISBN-13: 978-1-934355-26-8

Police detective Claire Cassidy was disillusioned after twelve years pursuing young people - often the same ones repeatedly - in the decaying steel town of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. The story mainly follows the case of one teenage girl gang who rob a convenience store. Using her usual police methods, things don't go well, until she meets the vice-principal of the girl's school. He is trying to introduce restorative practices there, although his principal believes in zero tolerance. The policewoman is also sceptical, but the v-p perseveres (he has a remarkable amount of time to devote to this single case!) and a restorative meeting is held. He does a bit of explaining, and doubts the effectiveness of punishment (p. 54, 56), although the offender's mother accepts it (p. 205); but the tone is not didactic, and the dialogue, including the meeting itself, sounds realistic to an English reader. The victim is still angry, and there is no instant reconciliation. Given the sub-title, we know that it will work out, but there are some credible doubts and setbacks along the way, and some unanswered questions at the end. The story held my attention in a way that a case history would not have done; I recommend it as a good read, with a realistic introduction to restorative practice as a bonus.

Martin Wright is a restorative justice author and practitioner. He is a recipient of the European Forum for Restorative Justice (EFRJ) Award for his contributions to restorative justice over many years.

Margaret Murray's Forging Restorative Justice can be purchased in the IIRP Bookstore. For the UK and Europe, use IIRP Europe's Bookstore.

Restorative Works Year in Review 2024 (PDF)

All our donors are acknowledged annually in Restorative Works.