Tim Newell, governor (retired) of Grendon Prison, U.K., explores the organizational paradigm of prison culture, to shed light on how the very different and potentially valuable restorative justice paradigm can be implemented in prisons. Newell oversaw the successful implementation of restorative justice practices in prisons, involving prisoners in taking personal responsibility for their offending and seeking to make reparation. The paper was presented at "Dreaming of a New Reality," the Third International Conference on Conferencing, Circles and other Restorative Practices, in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA, August 8-10, 2002.

Plenary Speaker, Saturday, August 10, 2002

From "Dreaming of a New Reality," the Third International Conference on Conferencing,

Circles and other Restorative Practices, August 8-10, 2002, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Restorative approaches to crime and conflict resolution represent a cultural challenge to the attitudes and assumptions that dominate prison governance and dynamics. These approaches have developed through the inherent conflict involved in keeping people in custody against their will. They are also rooted in historic values that have become accepted in the way that criminal justice systems regard serious offenders - those who are considered to need to lose their freedom so that society can feel safe. To approach working in restorative ways in prisons - and in particular using circles and conferencing approaches - calls for an examination of the tensions between the paradigm of current penal practice and that of restorative justice. Unless one recognises the difference it is likely that much effort will be spent in trying to enter or change a system that is heavily dependent on processes that do not fit with those of restorative justice. The function of the paradigm - which all organisations and bureaucracies have - is to maintain the purpose for an organisation’s existence. The dynamics of bureaucracies are self-preserving and preoccupied with internal processes of enforced compliance and maintenance of control systems. The reality is that RJ can assist the prison system develop many of the matters with which it is concerned. But the fundamental threat to the prison paradigm, and therefore the prison’s resistance to accept another paradigm must be recognised. The problem-solving approach of RJ has much to offer. To succeed in this involvement the dynamics of culture change should be recognised.

Restorative approaches are developed in order to promote three goals; to enable victim, offender and community to work together to understand what happened in the crime/conflict; to realise who has been affected by the events; and to decide together what should happen in order to repair the harm. To introduce such practice into prisons where the most serious offenders are isolated from their communities and out of possible contact with their victims - those who have been most seriously victimised - provides an opportunity to involve the processes of restorative work to address the issues they are anxious to change. Thus it is possible to see restorative work as a culture-changing process for those prisons that wish to become more effective in meeting the long-term needs of offenders, victims and their communities. Restorative work also enables prisons seeking to create a more harmonious environment for prisoners, their families and for staff and management.

Organisational and Cultural Change

In considering the potential of restorative approaches at work in prisons it is helpful to have a sound model of organisational and cultural change. By ‘sound’ I mean one that will enable us to see where to act in the system in order to support and develop change in meeting the needs of prisons effectively. The prison services are often dissatisfied with certain manifestations of their culture and seek to change them. They are dissatisfied with the levels of violence in prisons, the level of serious incidents, the environment of bullying and intimidation, and racial discrimination. The model has been developed with the Management School at Cranfield University. It provides us with a way of understanding complex organisations and systems facing change. We cannot understand the difficulty of achieving change in an organisation unless we are aware of the particular paradigm that holds the beliefs and assumptions grouped together into perceptual sets.

The Paradigm

The paradigm is an inevitable and vital feature of organisational life. If managed properly, it will encapsulate the distinctive competencies of the organisation and system within which it operates. Not only that, it will provide a formula for success that will allow the organisation to develop. If mismanaged, however, it will act as a conservative influence to prevent change. Indeed, it will cause strategic drift away from key objectives, and will lead to poor performance. Management of the paradigm can be achieved by attention to the organisational cultural web that surrounds and preserves the paradigm. By exploring the elements of the cultural web we can see what the paradigm of prisons is. The paradigm involves elements of security, punishment, deprivation, separation and survival as well as safety, respect, purposeful activity and resettlement procedures.

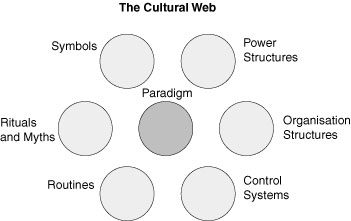

The Cultural Web

Study of organisations has led to an analysis of the factors that contribute towards the paradigm, or mind-set. These elements can be described as the cultural web. The elements, shown in the diagram, are interdependent and often very deep-rooted within the life and history of the organisation. The individual elements are explained in the following paragraphs and then related to the reality of prison experience.

Power Structures

Power structures describe the functional work of the organisation reflecting the effort and drive required to carry out the work; the power hierarchy of the organisation. The explicit structures reflect the formal arrangements as described; but within those structures are the informal power arrangements through representative and networking arrangements.

Prisons are places where power is very important in maintaining the balance of co-operation in the dynamic life of the institution. Of course, staff have obvious legal powers in order to maintain control of prisoners. Formal power of prison authorities is clearly established through legislation and powers given to staff to use force when necessary to maintain the integrity of the prison.

But there are also issues of legitimacy in the mindset of prisoners that make the experience acceptable to them. Prisoners have power too. Their powers derive from their numbers, from their compliance and involvement in the regime, and from their arranging of sub-cultural activities and relationships.

Significantly, RJ challenges the power structure of the separate sub-cultures in prisons. It does so by involving prisoners in taking personal responsibility for their offending and seeking to make reparation. All of this counters some of the culture of secrecy and close camaraderie. It implies a degree of overt power-sharing that can be very different from the expectations of many staff. It challenges the stereotyped perception that prisoners are not capable of exercising such personal power; it challenges the assumption that they remain in role of offender through denial, rather than break out from it through becoming responsible citizens. It also challenges the separation between staff and prisoners that is often a psychological survival necessity in systems of coercion and overload of numbers. The dynamic of a conference setting or circle in which all participants are considered able to make a contribution to the solving of the dispute challenges the normal approach of prisons in which management subconsciously seeks to develop dependency in prisoners so that they fit into the system of the institution.

Organisational Structures

The term ‘Organisational Structures’ refers to the formal arrangements made by the organisation to describe its working arrangements. Increasingly, these are flat structures with delayered hierarchies. In effective organisations they are open and organic, and reflect the rapidly changing emphasis of operations and priorities.

RJ works well within flat hierarchical structures. Nonetheless its more open approach to communication and sharing of issues in direct ways offers a challenge to prison expectations about secrecy and management information systems. This is because RJ expects people to be willing to give an account with openness and honesty, trusting others to work with the material in responsible ways.

Traditionally, structures are inevitably rectangular and divisive. This is because boundaries are essential for roles to be developed through organisations. Thus in this view, prisoners are at the bottom of the organisation, which the staff are organised to manage and control.

By contrast, RJ sees offenders as partners in the organisation of the conference/circle. Clearly, this represents a tension for many prisons. Despite this tension, partnership approaches are developing, not only in suicide prevention work, and educational programmes of peer counselling and more particularly in therapeutic communities that are developing in many prison settings.

RJ sees offenders as accountable to their victims, with an obligation to make right in some way the damage done. Traditionally, in contrast, prison sees itself as the penalty for the crime; technically, once the sentence is completed the prisoner has completed his obligation to society. Clearly there is tension in this difference.

Control Systems

The Control Systems of any organisation monitor the distribution of resources; they often constitute hard plans for the future work, defining priorities and key indicators of performance. They also contain soft systems such as induction programmes for staff joining the organisation and the appraisal system that connects individual commitment to the work of the organisation.

By contrast, RJ approaches can work in all systems if the approach is to be holistic about applying the principles. The use of RJ thinking in everyday life calls us to expect everybody to take responsibility for their actions and be willing to give an account when they are considered to have affected others. In the RJ approach, we expect Control Systems to be more consensual and with the agreement of all concerned.

RJ can be used in induction programmes to include staff and prisoners in the decision-making process, asking them to consider a problem-solving and inclusive approach to their custodial presence.

In the traditional system performance indicators of prisons are often concerned with output and outcomes. By contrast RJ is particularly concerned with process and with the values that inform that dynamic. Outcomes remain important of course. But they may take longer to achieve. That is because they involve the need to include all parties in the process of deciding. This tension between process and outcome can be marked at times.

Voluntary compliance with agreements is known to attain higher levels of implementation. RJ processes promote such controls that can contribute to the institutional reform agenda, which could reduce costs, improve services and deliver a more agreeable workplace.

Routines and Rituals

Routines and Rituals are often not described formally but are of day-to-day significance and reflect important relationships and activities. They reflect what an organisation celebrates and rewards in small but significant ways.

Prisons are very strong on routines and rituals. The ‘routine’ is the prison regime itself quite often. The need to survive the possibility of chaos places a strong imperative on staff to routinise many activities. Managing anxiety results in regularising activity and behaviour so that most people realise what is expected. The ‘daily miracle’ of the large local prison looking after 1400 people in a small confined setting is a case in point. Its ability to provide work, education, exercise, and association for most is indeed a miracle. The ‘bell’ is a celebration in many prisons, reward is often given to those who can understand and work within the rules - they are selected to be orderlies.

RJ has expectations that depend on the value of each person. Here, everyone has their say, only one person speaks at a time (with some token to mark the speaker), we celebrate the achievement of agreement and the possibility of transformation.

Myths and Stories

These are the stories told amongst members of the organisation about themselves as individuals and about the organisation as a whole. They describe the kernel of truth about the organisation; they reflect the values that prevail and which are perceived as dominant.

Each prison seems to have its own tradition - we do things our way. There is a real difficulty in learning from the practice of other prisons and from excellence in other settings. It comes down to a matter of emotional involvement and survival dynamics as to why each prison develops its culture and its cultural carriers. These ‘carriers’ are often the longest serving and most respected staff - not necessarily the senior ones. The ideal is when a manager can get into the position of being so respected. Stories often are to do with critical incidents and how the staff settled them or did not. Attitudes to prisoners and their families are developed through this tradition as well as through experience of success or failure in working together.

RJ will gain the confidence of participants through the successful involvement of people in the process. Although it sounds very rational and common sense, the experience of involvement is not something that can be explained or prepared for.

Stories and celebrations are to do with the achievements of satisfaction by victims, by the powerful experience of understanding between victim/offender and community members.

Symbols

These are the significant elements, ‘signs’ and ‘emblems’ that the members of the organisation recognise as standing for them. They can include the leaders of the organisation and often include symbolic acts of particular significance and include physical features - logos, uniforms, standardised design and architecture.

Prisons have many strong symbols: the wall, the gate, the uniform (of both prisoners and staff), the rule book, the hierarchy, the description of being Her Majesty’s Prison, the Centre of the prison and so on.

RJ too has its symbols. A major symbol is the circle. Others are the agreement, the facilitator (entrusted with the leadership of the process), the handshake, the talking stick and the contract that it implies among all listeners.

Achieving Change

Traditionally, strategic change within an organisation has focused on the first three elements as being the most recognised and easily influenced areas of work: power structures, organisational structures, control systems. However, it is often the case that the latter three elements - routines and rituals, myths and stories, symbols - may resist strategic change. This is particularly so if it challenges their ‘truths’ and their existence. These are more difficult areas to address as they are rarely talked about in organisational culture. They are taken for granted and are deeply incorporated into members’ concepts of belonging and not.

In order to be effective, strategic change must affect all six elements of the cultural web. Managers and those who seek to reform should address all elements over time in order to ensure that the change they perceive as required has a lasting effect and is fully incorporated into the life of the organisation and leads to a change of the culture.

The cultural web can be used to identify what features of the criminal justice system must be addressed if change is to be brought about successfully in restorative ways.

There are clearly some areas where it is possible to detect changes in the elements of the cultural web that may contribute towards the change in the paradigm. The original paradigm was centred on the need to protect the public (or an elite and powerful section of the public) through a careful consideration of the risks offenders represented. The means through which this risk was considered reflected the culture of retribution. Prison, as the most serious penalty for offenders, represents the most psychologically painful expression of our disapproval. As we seek to make prisons more effective in restoring prisoners to community living, there is a need to counter all the repressive elements that have formed the paradigm over the years. The change towards a more restorative paradigm or culture can be seen to be emerging in some aspects of our approach towards community justice. The process through which this is done will afford the individual prisoner power to accept responsibility and to influence the outcome of the process in a more direct way than ever before. There are signs that a major paradigm shift is possible as we realise the potential of greater movement in the culture within which offenders and victims are considered.

Practice in Prisons

In considering the application of restorative ideas in prisons we could use the model of the cultural web. Through this we could audit the way in which changes are already taking place in some prisons and how more could be achieved through this methodical approach towards cultural change. Restorative practitioners are beginning to work more in prisons and this effort could be considered through the model of the cultural web so that the work is effective within the context of the project but also in affecting the wider prison community.

The way that some of this work has been approached has influenced the functional areas of work described below. This work has been achieved by prison staff being dissatisfied with traditional ways of operating and realising that through restorative practice a more satisfactory process could be developed with more just outcomes.

Through audit and developing practice it is possible to see there are opportunities in the following areas of functional activity in prisons:

Induction programmes for prisoners. Establishing norms through staff and peer tuition and example, through setting standards and developing expectations of taking responsibility during the sentence can be very effective at the start of the sentence when prisoners are often at their most sensitive and receptive.

Complaints and requests systems. When the requests and complaints of prisoners are considered through an open process of mediation and direct communication in order to establish what happened, who was affected, in what way, and what should be done to put things right. This can be in contrast to some current practice that is often secretive in process and unsatisfactory in outcome for all parties.

Adjudications. Disciplinary hearings form a critical focus of many prison systems. How infractions of the rules are considered by the prison sets the tone of staff attitudes and prisoner compliance in many prisons. To offer an alternative process of a circle is a dramatic way to express the concept of staff and prisoners working together to resolve conflicts rather than reacting stereotypically to them. This process can be seen to gain a win-win setting, rather inevitable win-lose one of blame and scape-goating.

Anti-bullying strategy. This work when informed by RJ principles is based on developing an awareness of behaviour and confronting bullying through conferencing - rather than by removing the victim -which is sometimes seen as the solution. To develop a culture in which there is some challenge to the control systems of prisoners’ norms of secrecy is not easy but can be achieved through consistent application by staff of processes that make it safe to be honest.

Race relations. Similar handling of equal opportunity issues through open ways of mutual respect can establish for staff and prisoners that such matters are taken seriously. Their concerns will be handled fairly and openly whenever possible, recognising the perceived victim’s feelings and willingness for such a process.

Anti-violence strategy. The same considerations apply as for the anti-bullying strategy. The strategy to be developed could well include training for staff and prisoners in conflict-resolution awareness and skills, perhaps through a programme like the AVP (Alternatives to Violence Project). The establishing of peers mediators, as with the ‘listeners’ programme for suicide prevention and the peer education tutoring scheme will play to the strengths of many prisoners in managing difficult settings and in being able to support each other.

Preparation for release. When sentence planning is done in partnership with prisoners many RJ possibilities arise for accepting responsibility for the crime, establishing some accountability for the future to victims, primary and secondary, and a commitment to the community to which prisoners will return. The resources of the prison - work, education, leisure, offending behaviour courses and other programmes - can be channelled to this effect.

Offending behaviour courses. Victim empathy and accountability for criminal behaviour are expressed in these programmes in which prisoners take responsibility for their behaviour. This is the ideal setting for voluntary compliance, honesty and contrition to be expressed.

Resettlement. Preparation for resettlement should start early in the sentence and should engage the agencies that are likely to be affected by the prisoner’s release, such as housing, health, and employment, as well as the criminal justice agencies of police and probation. On the home leave or temporary release from prison the possibility of a conferencing of agencies including justice ones with the prison providing some feedback about the course of the sentence and about future expectations. Family and victims could be involved in this process that is focussed on the issues of returning to the community.

Circles on release. Once released the prisoner often experiences difficulties in sustaining the plans and the intentions when in custody. There is sometimes a need to provide some community support and involvement through a formal Circle of Support and Accountability.

Prison Outreach. Staff and prisoners can serve the community by educating groups about the effect of imprisonment through sharing of information about prisons and about the life stories of offenders.

Staffing processes. In order to integrate RJ practices, principles and processes into the prison’s life it is important that prison staff feel that they are treated with the same respect and consideration. Thus dispute and conflict resolution procedures should be developed offering mediation and conferencing for staff with trained facilitators. The personnel management of staff should operate with the same principles of concern for the individual and the respect for their personal development with the professional setting.