News & Announcements

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

Andrew Shaw, writing in the York Dispatch, reports that "Four York County [Pennsylvania] schools received state grant funding to prevent and reduce incidents of violence."

Andrew Shaw, writing in the York Dispatch, reports that "Four York County [Pennsylvania] schools received state grant funding to prevent and reduce incidents of violence."

One of the four schools, Crispus Attucks YouthBuild charter school, "is working with Bethlehem's International Institute for Restorative Practices. The institute will train YouthBuild teachers with its 'Safer, Saner Schools' [sic] program to reduce 'incidents of misbehaviors, expulsions, bullying and student absenteeism,' according to principal Melissa Bupp.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

The New York Times Magazine published a lengthy and very moving story January 4 by Paul Tillis about a restorative justice conference, which took place in the wake of a gun murder of a young woman by her boyfriend in Tallahassee, Florida. I couldn't begin to excerpt any of this story. But I recommend that it be read here and that the video below, of interviews with the parents of both victim and offender, be watched.

https://www.today.com/embedded-video/mmvo701261891721

From the Today Show January 7, 2013.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

Les Davey, director of IIRP UK & Ireland, writes:

In partnership with the City of Salford, IIRP UK & Ireland are pleased to announce their Summer 2013 Conference: "Restorative Practice: The way forward in Salford" to be held at Salford City Stadium, Manchester, on Thursday, 20th June 2013.

We are pleased to announce that Transforming Conflict is collaborating with us in planning a workshop stream. Both organizations are exploring closer collaboration where possible, as we share so many core values, principles and practices. This event will replace Transforming Conflict’s annual conference "Restorative Approaches in Educational and Care Settings" Conference for this year.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

Here's a 48-minute video produced by Heartspeak Productions with the Community Justice Initiatives Association from the Fraser region of British Columbia. The film discusses Canadian law and constitution and human rights as a fundamental basis of law. The film examines the effectiveness of punishment and deterrence, as well as alternatives including restorative justice and diversion. It argues that restorative justice can fulfill the human rights obligations embedded in Canadian law and also be more effective. While this film focuses on the Canadian system, there are many ideas that will be relevant to law and criminal justice in other countries.

The video can also be found at the following link:

Restorative Justice is the LAW | CJIBC.

- Details

- Written by IIRP Staff

This article recounts a great story in which a restorative circle was used to address conflict with about 20 girls in an alternative school in Maryland. Joe Burris of the Baltimore Sun writes:

This article recounts a great story in which a restorative circle was used to address conflict with about 20 girls in an alternative school in Maryland. Joe Burris of the Baltimore Sun writes:

It began as many confrontations between students do: with a hard stare between two passing strangers, according to Toni Holmes, a senior at an Ellicott City alternative school. One of the girls told a friend, "I don't like her." Snide remarks about clothing and appearance went back and forth, and then other girls chimed in.

Soon, unexplained yet simmering enmity exploded into a series of face-to-face confrontations among about 20 girls at the Homewood Center. Teachers got hurt preventing the arguments from becoming physical, and hallways were often deemed unsafe.

- Details

- Written by Laura Mirsky

Following up from the IIRP UK & Ireland 2012 Conference in partnership with City and County of Swansea: “Putting Theory into Practice: The Restorative Way” at Liberty Stadium, on Thursday 29th November, below are links to PDF files of the Plenary and Workshop Presentations submitted by presenters so far.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

The National Center on Family Group Decision Making has a new home at the Kempe Center for the Prevention and Treatment of Child Abuse and Neglect in Denver, CO. Previously with the American Humane Association, the Center has a new web site, which can be found at http://www.fgdm.org.

The National Center on Family Group Decision Making has a new home at the Kempe Center for the Prevention and Treatment of Child Abuse and Neglect in Denver, CO. Previously with the American Humane Association, the Center has a new web site, which can be found at http://www.fgdm.org.

The new site explains, "Family Group Decision Making (FGDM) recognizes the importance of involving family groups in decision making about children who need protection or care, and it can be initiated by service providers and/or community organizations whenever a critical decision about a child or youth is required. In FGDM processes, a trained coordinator who is independent of the case brings together the family group and the service providers to create and carry out a plan to safeguard children and other family members. FGDM processes position the family group to lead decision making, and the statutory authorities agree to support family group plans that adequately address agency concerns."

The National Center on FGDM has been a longtime friend of the IIRP, and worked together in 2004 to produce the Family Voices video, which lets families who have been through the FGDM process, a restorative practice, speak for themselves about the process and the impact it had on their lives.

The Center announces that its next "FGDM and Other Family Engagement Approaches Conference" will be held in Eagle County, Colorado on June 10-13, 2014, with a call for proposals expected in February 2013. An eForum post on the keynote from the last conference can be found here.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

Family Learning Signature (a Restorative Practice approach) at Carr Manor Community School, Nov 2012.

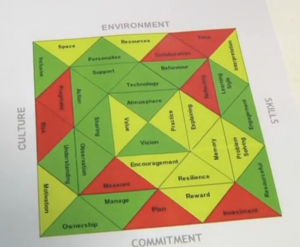

Example of a completed Family Learning Signature

Example of a completed Family Learning Signature

In the caption for this video, Leeds City Learning Centres writes, "The Family Learning Signature is a simple self assessment tool which generates information about how a family ‘learns’ together. As we know, the ability of any individual to embrace learning and manage their own development is greatly influenced by the collective capacity and skills of the family. In identifying strengths, and areas to be developed, a family is assisted in its own learning development including an understanding of inherent resources which drive behaviour and attitude."

In the video Gregor Rae, chair and CEO of BusinessLab, the company based in Aberdeen, Scotland that developed the learning signature, says, "What we see is a kind of increasing interest internationally in the role of the signature as part and parcel of restorative practice. I think it’s mainly because it’s such an effective tool for engaging the families. ... It gives you tremendous insight into the kind of dynamics of the family, particularly the learning dynamics of the family."

The video can also be seen at Vimeo through the following link: Family Learning Signature (a Restorative Practice approach) at Carr Manor Community School, Nov 2012

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

Students with Dignity in Schools t-shirts ushered into an 150-person overflow room, which would also fill up

Students with Dignity in Schools t-shirts ushered into an 150-person overflow room, which would also fill up

The Washington Post's Donna St. George reported on the Senator Durbin's "School-to-Prison Pipeline" hearing in the US Senate last week. The article begins:

At a congressional hearing billed as the first-ever focused on ending the “school-to-prison pipeline,” Edward Ward emerged as a voice of experience.

Ward, a recent high school graduate from Chicago, recalled classmates suspended for failing to wear ID badges and security officers patrolling hallways. Arrests were so common that a police processing center was created on campus “so they could book students then and there,” he said at the hearing Wednesday.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

IIRP Canada and FaithCARE (Communities Affirming Restorative Experiences), a program of Shalem Mental Health Network, announce a three-day event February 5-7, 2013 for congregations interesting in building restorative cultures. The two organizations draw on five years of experience working with congregations as outlined in this article, FaithCARE: Creating Restorative Congregations, which includes stories about how the program has helped congregations, as well as interviews with program leaders.

IIRP Canada and FaithCARE (Communities Affirming Restorative Experiences), a program of Shalem Mental Health Network, announce a three-day event February 5-7, 2013 for congregations interesting in building restorative cultures. The two organizations draw on five years of experience working with congregations as outlined in this article, FaithCARE: Creating Restorative Congregations, which includes stories about how the program has helped congregations, as well as interviews with program leaders.

Event: Learning How to Grow Restorative Churches

When: February 5-7, 2013, 9 a.m. - 4:30 p.m.

Where: Queen of the Apostles, 1617 Blythe, Mississauga, ON L5H 2C3

Fee: Includes training and coaching. $400 before January 15, 2013; $425 thereafter. 10% discount for two or more registrants from one organization.

Restorative Works Year in Review 2024 (PDF)

All our donors are acknowledged annually in Restorative Works.