A family satisfied with their FGDM, the North American term for a Family Group Conference, from the Family Voices videoIn spring 2014, the Dutch parliament approved an amendment to the country’s Law on Child Welfare that gives every citizen of the Netherlands, as of January 1, 2015, the right to make their own plan first when social services has been called upon to intervene in the care of a child or adolescent.

A family satisfied with their FGDM, the North American term for a Family Group Conference, from the Family Voices videoIn spring 2014, the Dutch parliament approved an amendment to the country’s Law on Child Welfare that gives every citizen of the Netherlands, as of January 1, 2015, the right to make their own plan first when social services has been called upon to intervene in the care of a child or adolescent.

Rob Van Pagée, founder of the Dutch NGO Eigen Kracht Centrale, heralds the law as an important step in the development of what he calls the “new welfare state,” in which decisions that most affect people’s lives can be made by them and their communities of support.

“Citizens now have a right to first make a ‘family group plan,’” says Van Pagée.

According to the wording of the law, a family group plan is an “aid plan or plan of action as prepared by the parents, together with relatives, in-laws or others who belong to the social environment of the youth.” The only exceptions would be made when parents have declined the opportunity to be involved in making such a plan or when the safety of the child is deemed at risk.

“Nobody can make a plan for me,” Van Pagée continues. “I have the right as a citizen to make that plan first, for myself. The way I make that plan is not stated in the law. It isn’t that everyone has to go through our organization, but the principal is in the law. You can make the plan first yourself; you have that right.”

Eigen Kracht has played a key role in advocating for this change to Dutch law. To date, it has organized over 10,000 family group conferences (FGCs) throughout the Netherlands. FGCs provide a structure to bring together extended family, close friends, and sometimes appropriate members of the community, to help a family or individual develop a plan to care for a child, secure housing, find work, confront addiction, obtain medical assistance or address other crucial issues that might affect children or youth in a family, rather than a judge, social worker or other professional making a plan for them. FGCs are also being used around the world in schools, prisons, communities and other contexts.

Eigen Kracht has a database of 800 trained independent coordinators throughout the country: paid citizen volunteers who may facilitate several FGCs each year. These coordinators often have jobs that have nothing to do with social work.

The key, says Van Pagée, is that families have a choice of coordinators in terms of cultural background and/or language. At the same time, the community coordinators are independent — meaning they have nothing to do with the plan and no interest at all in its outcome.

At the beginning of an FGC, the community coordinators do invite social services and other agencies to present the concerns of the state, which sometimes are requirements of the plan, and also explain services that might be available to families. But after those matters are explained and questions are answered, the professionals leave the room, as does the coordinator, and the family meets alone to develop their plan.

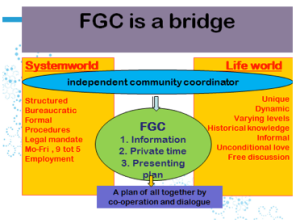

Why is it so important for coordinators to be from the community and independent, and for families to make their own plans? Van Pagée argues that “an independent coordinator is taking orders from nobody. Their only role is to facilitate the decision-making process, which an FGC is, and make sure that everybody receives the accepted plan. In this way an FGC is an independent bridge between the world of citizens – family and friends – and the world of professionals, who have the authority to intervene.”

Why is it so important for coordinators to be from the community and independent, and for families to make their own plans? Van Pagée argues that “an independent coordinator is taking orders from nobody. Their only role is to facilitate the decision-making process, which an FGC is, and make sure that everybody receives the accepted plan. In this way an FGC is an independent bridge between the world of citizens – family and friends – and the world of professionals, who have the authority to intervene.”

Additionally, writes van Pagée, “families have a lot of knowledge that the authorities don’t have” (2014, p. 1). Families have resources they are willing to use and come up with ideas the professionals never would have thought of or been able to support. Often these ideas save the state money because services performed voluntarily by family and friends are not billed to the state.

For example, the Amsterdam Youth Protection Agency recently learned that a family with a six-month-old baby was about to be evicted from their home. As immigrants — the father from West Africa and living in the Netherlands illegally, the mother from another part of Europe — the family had few resources and little recourse. An Eigen Kracht coordinator from the Nigerian community met with the family. (Coordinators from the family’s culture, who speak their language, are used whenever possible.) The family agreed, though without much hope, to participate in a conference. The coordinator asked them and a friend who should be invited to attend the conference and help make a plan. The coordinator reached out to a chief from the Nigerian community, and the family also received help from a friend to pay membership dues to an African community union, which was discovered during the conference-organizing process.

When the conference convened, the day before the eviction was to take place, the participants included two tribal chiefs from the African community along with people they invited, a friend of the family who attended the meeting by Skype and two social workers. To the surprise of everyone, the meeting resulted in a solid plan. The family was offered a temporary apartment and help moving immediately, free of charge. The professionals were asked to issue an “urgency statement,” which would give the family eligibility for permanent housing assistance when it became available. Everyone agreed to the plan and applauded the process. The resources of the family and community were harnessed successfully, along with the available professional services, to secure for the family what the state alone could not.

Another limitation of professional services is that despite the best intentions of social workers, government systems tend to utilize whatever programs they create, whether or not they actually suit the needs or demands of the people they serve.

Van Pagée recalls a situation when he was a young social worker and his boss said to him and his colleagues, “‘Guys, we now have this wonderful new project. We can take complete families in; we have treatment for them. It’s a better approach. I don’t understand why it’s empty.’ We understood this comment as an exhortation to bring in clients, and we succeeded in a few months. Whose need was fulfilled?”

Within the new welfare state, argues van Pagée, “the focus is on activating families and their networks first and asking for their resilience. The services then are answers to what family groups ask for. In our experience, family plans rely 80% on their own resources and 20% on requested services.”

“No one has done a more exemplary job of achieving and sustaining system change than Rob van Pagée,” writes IIRP President and Founder Ted Wachtel in the latest issue of Restorative Justice: An International Journal.

In his article, Wachtel writes that the Dutch example can provide a model for restorative practitioners and advocates worldwide. Eigen Kracht’s Family Group Conference model, along with the new Dutch law, provide an example of how a society can limit the power of the system and allow more control to be retained by the lifeworld.

“Science and Charity” by Pablo Picasso (1897)Wachtel explains, “These two terms were juxtaposed by Jürgen Habermas [a German sociologist and philosopher] to represent two competing but related explanations of how society operates. The system is modern society with its administration, laws, politics, economy, organisations and paid professionals, while the lifeworld is community, a network of relationships among family and friends who, unlike those in the system, look out for each other because they care, not because they are paid money to do so” (Wachtel, 2014, p. 361). Frank Früchtel, a professor in the Department of Social Work at Potsdam University of Applied Sciences, Germany, illustrated the contrast between the system and the lifeworld by projecting images of two oil paintings (see illustrations) during a keynote at the IIRP’s 12th World Conference in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA, in 2009. Each painting shows a person on their deathbed. In the first, a professional physician monitors the vital signs and a nun cares for a child. No other family or friends are present, and the atmosphere is cool and sterile. In the second, the patient is no less ill, but the scene is lively. Three generations are represented, including the patient’s son and children, and even the family dog, all offering help and love in a manner appropriate to their age and relationship.

“Science and Charity” by Pablo Picasso (1897)Wachtel explains, “These two terms were juxtaposed by Jürgen Habermas [a German sociologist and philosopher] to represent two competing but related explanations of how society operates. The system is modern society with its administration, laws, politics, economy, organisations and paid professionals, while the lifeworld is community, a network of relationships among family and friends who, unlike those in the system, look out for each other because they care, not because they are paid money to do so” (Wachtel, 2014, p. 361). Frank Früchtel, a professor in the Department of Social Work at Potsdam University of Applied Sciences, Germany, illustrated the contrast between the system and the lifeworld by projecting images of two oil paintings (see illustrations) during a keynote at the IIRP’s 12th World Conference in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA, in 2009. Each painting shows a person on their deathbed. In the first, a professional physician monitors the vital signs and a nun cares for a child. No other family or friends are present, and the atmosphere is cool and sterile. In the second, the patient is no less ill, but the scene is lively. Three generations are represented, including the patient’s son and children, and even the family dog, all offering help and love in a manner appropriate to their age and relationship.

“The ‘lifeworld’ presents an apt metaphor for restorative practices,” says Wachtel.

"Filial Piety" by Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1763) illustrates the atmosphere of Habermas's "lifeworld"

"Filial Piety" by Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1763) illustrates the atmosphere of Habermas's "lifeworld"

Wachtel argues that in the same way that FGCs return decision-making power to family and friends, restorative conferences, which are used to respond to crime and harm, return responsibility to victims, offenders and their respective communities of care. For instance, writes Wachtel: “When Judge Barry Stuart of the Yukon Territorial Court removed his judicial robe, stepped down from the bench and took a seat in a sentencing circle comprised of family and neighbours of the accused, he moved away from ‘the system’ and toward ‘the lifeworld’ ” (2014, p. 361).

But while there are many examples of individuals, organizations and communities that initiate programs to engage stakeholders in major decisions, few are able to sustain that change. Wachtel warns, “Implementing change with fidelity to restorative principles and then resisting the tendency to drift back toward the system are significant challenges facing restorative practitioners everywhere” (2014, p. 361). Eigen Kracht, he says, provides an example of an organization that has been successful.

Van Pagée is cautious, however. He says that just because there’s a law in the Netherlands stating that everyone can make their own family plan doesn’t mean that everybody knows that. They may not be offered the opportunity unless they ask for it. Or they might be discouraged by a well-meaning but over-protective social worker who says, “You don’t really want to make your own plan, do you?”

Still, he says, “No one can deny that such a law exists now.” And in the meantime, he and Eigen Kracht continue the work of educating professionals and the public about what an FGC is, and that it is now their right as a citizen of the Netherlands to ask to make their own plan before one is imposed upon them by the government.

References

Van Pagée, R. (2014). Transforming care: The new welfare state. European Forum for Restorative Justice Newsletter, 13(2), 1–4.

Wachtel, T. (2014). Restorative justice reform: The system versus the lifeworld. Restorative Justice: An International Journal, 3, 361-366.

Subscribe to Restorative Justice: An International Journal.

Rob van Pagée will be presenting at the IIRP Europe Conference in Budapest, Hungary, June 10-12, 2015. The IIRP is currently developing a partnership with Eigen Kracht to provide training on the Dutch organization’s FGC model.

Watch a 3-minute trailer of “Letter of the Mayor,” a documentary showing the application of an FGC to enhance relationships in a community facing a number of problems.