News & Announcements

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

This month the Public Broadcast System in the United States is showing a documentary film titled Fixing Juvie Justice. The film provides a critique of the revolving door of youth justice, and its criminalizing effect on many youth who originally commit very minor crimes. Then it turns to an examination of restorative justice as an alternative model, and discusses some of the roots of conferencing in New Zealand.

This month the Public Broadcast System in the United States is showing a documentary film titled Fixing Juvie Justice. The film provides a critique of the revolving door of youth justice, and its criminalizing effect on many youth who originally commit very minor crimes. Then it turns to an examination of restorative justice as an alternative model, and discusses some of the roots of conferencing in New Zealand.

Dr. Lauren Abramson, founder and executive director of the Community Conferencing Center in Baltimore, Maryland, USA, and Assistant Professor of Child Psychiatry at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, is quoted throughout the video. She was a student of Sylvan Tomkins, whose theory of affect has been very useful for helping to explain what happens in a restorative conference. Abramson also describes her personal quest to find a better way to work with criminal offenders, especially young ones.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

I was struck by the sincerity of this post by an anonymous offender who opts for a restorative justice meeting with the person he victimized:

Photo of Don Jail, Toronto by Mark Watmough at Flickr Creative Commons.

Photo of Don Jail, Toronto by Mark Watmough at Flickr Creative Commons.

I wanted to tell people what restorative justice means to me, as someone who has been through the whole process.

In prison, I made so many steps to change and I thought that there was something not there, something that was missing. That’s when I heard about restorative justice. I thought about how my victim felt and so I got involved with it. I wasn’t expecting to get as much out of it as I got out of it.

When I got out of jail and met my victim, it was a really big shock. I would never put anybody through that again. I can say that because I have been through restorative justice and I know how it affects them. I can recommend it [restorative justice] to anybody who is thinking of changing.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

There are so many lovely short videos now that demonstrate restorative approaches in schools. This one features the voices of many students as well as staff and administrators at two schools in Greater London.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

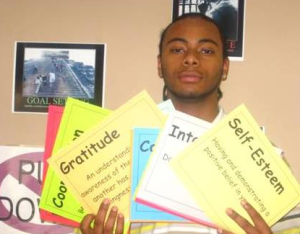

A youth recognized for displaying all 15 character traits as part of the Evidenced Based Aggression Replacement Training Program (photo from the Tennessee Department of Children Services Web Site)Aggression Replacement Training® is a new IIRP event which explores how to reduce violence and youth aggression for those working in education, criminal justice, social services and youth counseling. The Aggression Replacement Training process involves engaging and empowering aggressive youth to take responsibility for their behavior and learn healthier ways of interacting with others.

A youth recognized for displaying all 15 character traits as part of the Evidenced Based Aggression Replacement Training Program (photo from the Tennessee Department of Children Services Web Site)Aggression Replacement Training® is a new IIRP event which explores how to reduce violence and youth aggression for those working in education, criminal justice, social services and youth counseling. The Aggression Replacement Training process involves engaging and empowering aggressive youth to take responsibility for their behavior and learn healthier ways of interacting with others.

Dr. Craig Adamson, Assistant Professor at the IIRP Graduate School and Executive Director of Community Service Foundation/Buxmont Academy, IIRP's demonstration projects for at-risk youth, said that Aggression Replacement Training is an evidence-based restorative practice that has demonstrated success over the past two years with youth in the CSF Buxmont programs. "What I like about Aggression Replacement Training," said Craig, "is that it's very restorative. It's engaging and empowering. Aggression Replacement Training talks about how youth relate to all the stakeholders in their lives and how to engage appropriately with one another. It also looks at what happens with shame, how you can identify your own feelings in the moment, and it is very explicit with kids."

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

Pierre R. Berastaín, a student at Harvard Divinity School and co-founder of the Massachusetts Restorative Justice Collaborative, writes today on his Huffington Post blog:

C4RJ police partners gather for restorative justice legislative hearing at the Massachusetts State House. Left to Right: Sgt. Matt Pinard (Littleton), Lt. Leo Crowe (Carlisle), Det. Mike Sallese, Chief Robert Bongiorno (Bedford)

C4RJ police partners gather for restorative justice legislative hearing at the Massachusetts State House. Left to Right: Sgt. Matt Pinard (Littleton), Lt. Leo Crowe (Carlisle), Det. Mike Sallese, Chief Robert Bongiorno (Bedford)

While restorative justice programs continue to sprout throughout the state, no law has helped promote or endorse any of them. This legislative session, however, State Sen. Jamie Eldridge (D-Acton) has introduced Senate Bill 52, an act promoting restorative justice practices. If it goes into law, the act would not only give legislative recognition and legitimacy to restorative practices, but it would also establish a committee to assess programs in the state as well as make recommendations for future programming. This committee would bring together a range of representatives, from court-based programs to community members and academics in the field. For us in the Massachusetts Restorative Justice Collaborative, an organization that seeks to sustain the existing momentum and nourish a more cohesive restorative justice movement throughout the Commonwealth, the Act would further establish our efforts to bring restorative and transformative practices to a number of settings including schools, shelters, and prisons.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

Janine P. Geske, retired Justice of the Wisconsin Supreme Court and Distinguished Professor of Law at Marquette University Law School, recently spent time as a Visiting Professor in Restorative Justice at Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium. She has written two blog posts for Wisconsin Restorative Justice Coalition inspired by her time abroad. In the first piece, she discusses the framework for national implementation of restorative justice (mostly mediation) processes in Belgium. In the second second, she suggests ways American researchers and advocates could learn from their European colleagues. (Thanks to IIRP's Wisconsin affiliate, Patrice Vossekuil, for forwarding the link.)

Janine P. Geske, retired Justice of the Wisconsin Supreme Court and Distinguished Professor of Law at Marquette University Law School, recently spent time as a Visiting Professor in Restorative Justice at Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium. She has written two blog posts for Wisconsin Restorative Justice Coalition inspired by her time abroad. In the first piece, she discusses the framework for national implementation of restorative justice (mostly mediation) processes in Belgium. In the second second, she suggests ways American researchers and advocates could learn from their European colleagues. (Thanks to IIRP's Wisconsin affiliate, Patrice Vossekuil, for forwarding the link.)

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

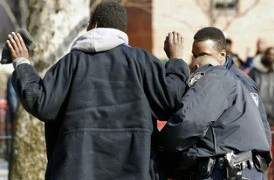

Stop and frisk policing, according to a new study, "stirs up, rather than deters, youth crime," according to an article in Time magazine. The following, by Nicole Flatow, published by the Center for American Progress, succinctly summarizes that article and the finding of the report:

Photo published at Think Progress

Photo published at Think Progress

Students who are stopped by police are more likely to later engage in delinquent activity, according to a new study in the journal Crime & Delinquency.

Researchers at the University of Missouri at St. Louis followed about 2,600 students participating in gang-prevention programs in seven different cities over the course of seven years. They subjected some students to random police stops, even when they hadn’t done anything wrong, some to stops and arrests, while others were not stopped.

According to a recap of the study by Time’s Maia Szalavitz:

By the end of the study, those who did have police contact early in the trial period reported committing five more delinquent acts on average, ranging from cutting classes to selling drugs and attacking people with a weapon, than those who were not stopped randomly by police. And the students who were arrested for any reason wound up committing around 15 more delinquent acts on average than those who were not. The rates held even after the scientists adjusted for the effect of age, race and previous delinquency that could also affect their odds of being targeted by the police.

The study also found that those who had police interaction had a change in attitude: they were less likely to feel guilty about the crimes they committed and more likely to rationalize their behavior.

This research has implications not just for police stop-and-frisks that have become rampant and discriminatory in cities like New York City. It also provides further evidence that criminalizing student disciplinary violations in what is known as the “school-to-prison pipeline” has counterproductive, long-lasting adverse effects on students’ development.

Another related Chicago study found that locking up youth similarly makes them more likely to offend again, as compared to kids who committed similar offenses but were not put in juvenile detention. And researchers in Montreal found even more striking results over the course of 20 years, with kids who enter the juvenile justice system even briefly twice as likely to be arrested as adults, and those who entered juvenile detention 37 times as likely to be arrested.

Read the original post at Think Progress.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

When the teachers at Country Day School, an American private school in Costa Rica, were trained in restorative practices several years ago, Veronika Marenco, a third grade teacher at the time, knew she had found something really useful. She started the school year with circles for her students to get to know one another, and followed it up every day with daily circles to check in and check out, play games, review math concepts and also address problems between students. A few weeks in, when parents were invited to "Back to School Night," Veronika even arranged the classroom in a circle of chairs and let parents (and a few children who came along) experience a circle to introduce themselves to one another.

When the teachers at Country Day School, an American private school in Costa Rica, were trained in restorative practices several years ago, Veronika Marenco, a third grade teacher at the time, knew she had found something really useful. She started the school year with circles for her students to get to know one another, and followed it up every day with daily circles to check in and check out, play games, review math concepts and also address problems between students. A few weeks in, when parents were invited to "Back to School Night," Veronika even arranged the classroom in a circle of chairs and let parents (and a few children who came along) experience a circle to introduce themselves to one another.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

Here's a five-minute "teaser" for a forthcoming documentary from Teachers Unite titled Growing Fairness. The first part of the trailer offers a critique of the so-called school-to-prison pipeline and zero tolerance policies.

- Details

- Written by Joshua Wachtel

Eric Assur at Restorative Justice Online has just posted a book review on Restorative Justice Today: Practical Applications, edited by Katherine S. van Wormer and Lorenn Walker. As I mentioned last fall, this book includes a chapter co-written by IIRP President Ted Wachtel and another written by IIRP Assistant Director for Communications Laura Mirsky.

Eric Assur at Restorative Justice Online has just posted a book review on Restorative Justice Today: Practical Applications, edited by Katherine S. van Wormer and Lorenn Walker. As I mentioned last fall, this book includes a chapter co-written by IIRP President Ted Wachtel and another written by IIRP Assistant Director for Communications Laura Mirsky.

Over the past thirty years the number of books or publications on Restorative Justice (R.J.) has increased annually. In 2013 justice practitioners, students and conflict resolution (or conflict prevention) readers may proclaim this publication as their book of the year. The authors, both with interesting backgrounds and academic credentials have provided a ‘practical’ look at the current applications for R.J. in the United States and elsewhere. Unlike most North American or United Kingdom anthologies with limited geographic focus this publication provides an impressive worldwide frame of reference. The words they use are well chosen and the entire collection of twenty five (25) articles by a well chosen collection of twenty nine listed authors is thoughtfully organized.

Restorative Works Year in Review 2024 (PDF)

All our donors are acknowledged annually in Restorative Works.