Stop and frisk policing, according to a new study, "stirs up, rather than deters, youth crime," according to an article in Time magazine. The following, by Nicole Flatow, published by the Center for American Progress, succinctly summarizes that article and the finding of the report:

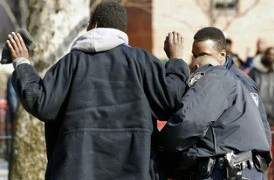

Photo published at Think Progress

Photo published at Think Progress

Students who are stopped by police are more likely to later engage in delinquent activity, according to a new study in the journal Crime & Delinquency.

Researchers at the University of Missouri at St. Louis followed about 2,600 students participating in gang-prevention programs in seven different cities over the course of seven years. They subjected some students to random police stops, even when they hadn’t done anything wrong, some to stops and arrests, while others were not stopped.

According to a recap of the study by Time’s Maia Szalavitz:

By the end of the study, those who did have police contact early in the trial period reported committing five more delinquent acts on average, ranging from cutting classes to selling drugs and attacking people with a weapon, than those who were not stopped randomly by police. And the students who were arrested for any reason wound up committing around 15 more delinquent acts on average than those who were not. The rates held even after the scientists adjusted for the effect of age, race and previous delinquency that could also affect their odds of being targeted by the police.

The study also found that those who had police interaction had a change in attitude: they were less likely to feel guilty about the crimes they committed and more likely to rationalize their behavior.

This research has implications not just for police stop-and-frisks that have become rampant and discriminatory in cities like New York City. It also provides further evidence that criminalizing student disciplinary violations in what is known as the “school-to-prison pipeline” has counterproductive, long-lasting adverse effects on students’ development.

Another related Chicago study found that locking up youth similarly makes them more likely to offend again, as compared to kids who committed similar offenses but were not put in juvenile detention. And researchers in Montreal found even more striking results over the course of 20 years, with kids who enter the juvenile justice system even briefly twice as likely to be arrested as adults, and those who entered juvenile detention 37 times as likely to be arrested.

Read the original post at Think Progress.