Paper by Daniel Van Ness, presented in a plenary session at "The Next Step: Developing Restorative Communities, Part 2," the IIRP''s 8th International Conference on Conferencing, Circles and other Restorative Practices, October 18-20, 2006.

This paper was adapted from a larger working document on RJ City and presented on October 18, 2006, at the IIRP Conference "The Next Step: Developing Restorative Communities, Part 2,� held at Bethlehem, PA.

|

Introduction

The RJ CitySM project is a research and design project to consider the possibilities and potential limits of restorative justice theory. Its purpose is to design a model justice system capable of handling all crimes, all offenders and all victims.

The project is being conducted in three phases:

- Design a written model of a restorative system.

- Create an interactive website to demonstrate the model; obtain feedback, suggestions and information about ongoing restorative justice programs; and identify areas of further development.

- Adapt the simulation into two products:

- A public policy instrument that can accept actual data from particular jurisdictions to demonstrate the feasibility of restorative justice.

- An educational simulation game that will teach students how to manage organizational change to bring about a restorative justice system.

This paper reflects work done to date on phase 1 of the project. We are in the process of building the website (phase 2) and anticipate it going live in October 2007. Phase 3 is dependent on receiving additional funding.

What is RJ CitySM?

RJ CitySM is a virtual city, located in a jurisdiction in which legislation was adopted ten years ago permitting the creation of “Justice Jurisdictions” whose borders are contiguous with the boundaries of cities with a population of at least one million people. The impetus for this change was a crisis of prison overcrowding due to the number and length of prison sentences in the state. Costs had risen to the point that educational and medical budgets were reduced, with further and more dramatic reductions forecast in succeeding years. These cuts were not popular among the voters, and it was hoped that the new legislation would halt the escalating criminal justice costs associated with crime within large cities.

A city became a Justice Jurisdiction by action of its city council. The implications of such a designation were significant. First, all state and county resources dedicated to responding to crime in that city would be placed at the disposal of the city council. This meant that the proportionate share of resources expended by state and county law enforcement, jails, prisons, probation, parole, prosecution, courts, criminal defense, victim assistance and so forth would be given to the city. In return, the city agreed to respond to all crime within the city without further state or county assistance. If any such assistance (such as forensic or investigatory experts, prison or jail space, and so forth) were required at any point in the criminal justice process, the city would be required to pay for it on a cost basis.

Because funds had been allocated already for prison construction, capital funds sufficient to build jails, prisons or other places of confinement were also available to Justice Jurisdictions. The funds provided were sufficient to house the percentage of state and county prisoners from that Justice Jurisdiction on the effective date of the legislation. The funds could be used for any capital project required to respond to crime within the Justice Jurisdiction’s boundaries. However, the Justice Jurisdiction then became responsible for all costs related to running those institutions.

Justice Jurisdictions are bound by the state’s criminal law, but the city council is authorized to establish levels of seriousness for each of those laws and to determine how the Justice Jurisdictions would respond to each level. It was possible for the city council to decline to enforce the least serious crimes, which would effectively decriminalize those offenses. Further, the city council could determine ranges of permissible sentences for each range, without being bound by any existing mandatory or presumptive sentencing laws in the state.

RJ City’sSM city council, following the recommendation of the mayor, applied for Justice Jurisdiction status. RJ CitySM qualified for such a designation, having a population of just over one million people. After community hearings, public debates, consultations, and widespread media coverage, the city council decided to adopt restorative justice as its philosophy of criminal justice. This was ratified in a public referendum. Over a period of years, it reorganized its criminal justice system until it was hardly recognizable. Whole departments were closed down and others created. Some staff were retrained for new positions, others decided to retire, and those who remained received substantial and, by all accounts, highly effective training on the definition, values and implications of restorative justice. Some funds that had been previously used in the criminal justice system were used instead to contract with local or citywide nonprofit organizations.

A few words should be added to explain why restorative justice generated this level of support. Several years prior to the referendum, one elementary school began using restorative interventions in dealing with student discipline. This approach not only reduced the number of students reported to the principal for disciplinary action, but it also created a learning environment in which students were able to learn better. After one year’s pilot, teachers and staff in all public schools were trained to use restorative processes, and restorative justice became the official approach to student discipline.

On occasion restorative practices were used in dealing with staff-administration conflict as well, and the approach was so successful that it was incorporated into the next teacher’s contract. This brought restorative practices to the attention of city officials, who decided after a few years to adopt these approaches in dealing with all disciplinary infractions involving city employees. This brought restorative practices to the attention of the business community, and several of the largest companies in the city decided to use restorative practices in their disciplinary procedures.

Meanwhile a coalition of nonprofit organizations began to promote restorative justice as a better way to deal with offending. Their initial work focused on juvenile offenders, and they found considerable support from police and social workers, who had seen the benefits of this approach in schools. But the group also launched a citywide public education campaign to generate public support. This campaign had several key features:2

- The organizers were careful to put together a diverse campaign-oversight team, beginning with those groups who were typically underserved by current juvenile justice policies. They looked within these groups for dynamic and charismatic leaders who could present restorative justice in a compelling way.

- They conducted a survey of resources currently available in RJ CitySM for dealing with juvenile offending.

- They created resources explaining restorative justice (videos, print materials, FAQ, etc.) and distributed these throughout the city.

- They identified potential supporters and opponents of restorative justice approaches, and individuals on the campaign team developed personal relationships with these individuals. They found that relationships were extremely important in generating support and in keeping their efforts from being divisive.

- They began a public education campaign that included presentations to groups, public education announcements on radio and television, stories in the newspapers and so forth.

- As interest in this restorative justice grew, they worked with the various players in the juvenile justice system to ensure that changes in policy were effected with comparable changes in funding priorities. This way, the new restorative justice programs had enough revenues to function well.

- When changes began to be implemented, the campaign team monitored and evaluated the process and results of those changes. This not only allowed them to publicize positive results, but also to identify reasons why the programs were not as successful in some areas as others. This allowed them to make changes in strategy or in personnel.

It should be understood that the citizens of RJ CitySM are normal people. While many have come, over time, to internalize the values of collaborative conflict resolution (and to become adept at resolving disputes restoratively), it should not be assumed that they are uniquely and uniformly committed to making restorative justice work.

Furthermore, the crimes that occur in RJ CitySM are similar to those that take place elsewhere. The offenders, victims, witnesses, even those who run restorative programs are susceptible to the same range of personalities, emotions, busyness, burnout and dilemmas as they would be in any other city.

In other words, restorative responses do not happen automatically. A structure has been required to refer cases and people to the appropriate programs, to inculcate restorative training and values, to mobilize the community as needed, and to monitor and evaluate the entire process. This section provides an overview of the Justice Network, which provides that structure in RJ CitySM.

We begin with the definitions, principles, values and goals adopted for RJ CitySM. Next, we present an introductory overview of the Justice Network. Finally, we consider ways of assessing whether the Justice Network and its contributing parts are providing a restorative experience to the people of RJ CitySM.

Definition

It is important to be explicit about the meaning of restorative justice as it is used in RJ CitySM. This provides the basis for developing and implementing restorative justice structures, and for monitoring and assessing them for restorativeness.

“Restorative justice” is sometimes used narrowly to refer to programs that bring affected parties together to agree on how to respond to crime (this might be called the encounter conception of restorative justice). It is used more broadly by others to refer to a theory of reparation and prevention that would influence all criminal justice (the reparative conception). Finally, it is used most broadly to refer to a belief that the preferred response to all conflict–indeed to all of life–is peace building through dialogue and agreement of the parties (the transformative conception). The following definition was adopted for RJ City: “Restorative justice is a theory of justice that emphasizes repairing the harm caused or revealed by unjust behavior. Restoration is best accomplished through inclusive and cooperative processes.”

Principles

Practices and programs reflecting restorative purposes respond to crime and other offenses by:

- Identifying and taking steps to repair harm. Three types of harm are typically associated with offenses. The first is personal harm: the material, physical, emotional, psychological, and/or spiritual harm experienced by victims, offenders and their communities. The second is relational harm: the harm done to the relationships between and surrounding victims and offenders (including to families, friends, neighbors and other members of their “communities of care”). The third is ethical or moral harm: the harms resulting when norm violations lead to losses of trust in fellow citizens and in authorities, causing loss of trust in fellow citizens and in the authorities’ capacity to secure public safety and order.

- Involving all stakeholders. The stakeholders in a society’s response to crime and other offenses include those who have been harmed or who have caused harm. These include victims, offenders, their “communities of care” (families and friends), their communities (neighborhoods and communities of interest) and their governments.

- Transforming the traditional relationship between communities and their governments. Communities and governments are two expressions of a society. They play complementary roles in responding to individual offenses, victims and offenders, as well as in working to prevent future crimes. The primary strength of a community in responding to crime and other offenses lies in caring networks of relationships characterized by mutual respect and commitment. The primary strength of government lies in its ability to ensure both civil order and orderly procedures, using force when necessary.

Values

The philosophy of restoration is deeply informed by the peacemaking approach to conflict. This approach values peaceful social life, characterized by respect, solidarity and active responsibility. Restorative justice seeks to reflect those values in the context of crime and other offenses. It does this by pursuing the operational values listed after each peacemaking value:

- Peaceful social life means more than the absence of open conflict. It includes concepts of harmony, contentment, security and well-being that exist in a community at peace with itself and with its members. Furthermore, when conflict occurs it is addressed in such a way that peaceful social life is restored and strengthened.

- Resolution: the issues and people surrounding the offense and its aftermath are addressed as completely as possible.

- Protection: the physical and emotional safety of affected parties is a primary consideration in all phases.

- Respect means regarding all people as worthy of particular consideration, recognition, care and attention simply because they are people.

- Inclusion: affected parties are invited to directly shape and engage in restorative processes.

- Empowerment: affected parties are given a genuine opportunity to effectively influence and participate in the response to the offense.

- Solidarity means a feeling of agreement, support and connectedness among members of a group or community. It grows out of shared interests, purposes, sympathies and responsibilities.

- Encounter: affected parties are invited, but not compelled3, to participate in person or indirectly in making decisions that affect them in the response to the offense.

- Assistance: affected parties are helped as needed in becoming contributing members of their communities in the aftermath of the offense.

- Moral education: community standards are reinforced as the values and norms of the parties, their communities and their societies are considered in determining how to respond to particular offenses.

- Active responsibility means taking responsibility for one’s behavior. It can be contrasted with passive responsibility, which means being held accountable by others for that behavior. Active responsibility arises from within a person; passive responsibility is imposed from outside the person.

- Collaboration: affected parties are invited, but not compelled, to find solutions through mutual, consensual decision making in the aftermath of the offense.

- Reparation: those responsible for the harm resulting from the offense are also responsible for repairing it, to the extent possible.

Goals and Strategies

Three goals shape a restorative response to crime. In order of decreasing importance they are:

1. Resolution: RJ CitySM seeks to repair the harms that result from crime, in ways that meet victims’ needs, require offenders to make amends and help both of them (re)gain full functioning as members of the community. The process of doing so identifies the injustice that took place and the steps the offender needs to take to make things right (now and in the future). Full restoration may not be possible, but the emphasis is on making progress toward resolution. Even when that proves impossible, at least the harms should not be made worse.

Strategies for accomplishing this goal include providing for party-to-party encounters, providing for encounters between the parties with the assistance of a facilitator and when needed, providing outside authorities to decide on how restoration and resolution can best be sought. The first two strategies are used when the parties choose to engage with each other in response to a crime. The third is limited to those times when an adjudicative component is required, either instead of or in addition to a cooperative process.

Within RJ CitySM, the constellation of programs, services and institutions that make cooperative and adjudicative processes possible are referred to as the “Resolution Sphere.” If the parties are unwilling or unable to reach mutual agreement using cooperative processes, the matter is referred to adjudicative processes. If necessary, coercion may be used in the adjudicative process to secure the presence of essential parties. However, at all times the parties are invited to initiate or renew efforts at a cooperative resolution. In addition, collaborative processes may take place within an adjudicative process, such as when a judge delays sentencing until the parties and their communities of care have engaged in dialogue about how the victim’s needs could best be met.

2. Community building: RJ CitySM seeks to respond to crime in such a way that all parties can be integrated into strong communities as whole, contributing members.

Strategies for accomplishing this goal include allowing the parties and their communities of care to recover from the harm and be integrated into the community on their own and without outside assistance. A second strategy is to provide assistance and active support from outside resources to help the parties and their communities of care to recover and be integrated into their communities. A third strategy is focused on the communities of the parties; here the communities themselves receive assistance in becoming better able to provide a prosocial, constructive and hospitable environment for the parties.

The first strategy can be accomplished by the party and his/her community of care alone. The second strategy requires assistance from community or government resources. The third strategy requires assistance to the community, which could come from within the community, from the government or from other external sources.

Parties are not coerced into using the available resources or into pursuing recovery or integration. Necessary resources, however, are available for those who choose to use them. This requires the presence of a range of programs and services, as well as compassionate community members, which parties can draw from. These services are available to all members of the community and not simply to those who have caused or suffered harm through criminal activities. Within RJ CitySM, this constellation of programs and individuals offering such resources and services is referred to as the “Community Building Sphere.”

3. Safety: RJ CitySM seeks to maintain a basic framework of safety within which to carry out restorative practices. Strong communities provide environments in which constructive relationships thrive and in which community peace, harmony and fairness is possible. However, some conflict and crime suppression requires more than strong communities; it requires the presence of governmentally administered order. Examples of this range from regulatory measures dealing with traffic, zoning and so forth to problems beyond the capacity of the community alone, such as serious illegal business practices, illegal gang activity, drug trafficking and so forth.

Strategies for accomplishing this goal include adoption of laws and regulations by democratically selected governments, self-enforcement of those laws and regulations by affected community members and suppression of crime by government authorities.

In RJ CitySM, the programs and agencies involved in pursuing these strategies are included in the “Safety Sphere.” Because restorative justice focuses on resolution and community building, order serves a more limited function in RJ CitySM than in more traditional criminal justice jurisdictions. Efforts to establish and maintain order are understood to provide a context for resolution and community building and to ensure a safeguard when other approaches to bring safety prove inadequate. While pursuing safety involves certain strategies and activities that are similar to contemporary police functions and programs (for example, traffic enforcement, police units focusing on illegal business practices, illegal gang activity, drug trafficking, serial crime and so forth), it differs in several ways as well. First, community participation and responsiveness are emphasized more than they are outside of RJ CitySM. Second, strategies to accomplish those limited purposes are viewed as temporary necessities that give way to more community-based and cooperative strategies when possible.

Overview of RJ City’sSM Justice Network

RJ City’sSM response to crime and other offenses emerges from a number of diverse and dynamic programs, systems, processes, boards, committees, movements, efforts, organizations, agencies, funds, neighborhoods, families, individuals and so forth.

These contributing parts must have sufficient structure, form and coordination to be predictable, protect the public interest and be responsive to stakeholder needs. However, there must also be sufficient flexibility for innovation, community leadership and involvement, along with adaptation to the preferences of stakeholders.

Some of the contributing parts are permanent, but the whole is, in many ways, changeable and even unpredictable as individual parts and members change, grow and interact. While those responsible for coordination have a large influence on the parts and members of the whole, the individual parts and members have a large and dynamic influence on those who coordinate. There is coherence, intricacy and life within what we will call the Justice Network.

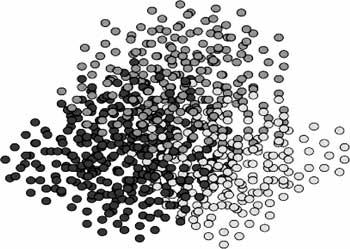

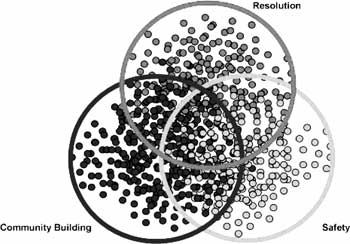

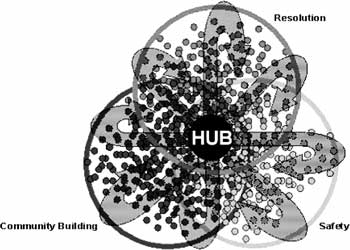

Here is a series of illustrations of the components that make up the Justice Network.

These component parts pursue one or more of the three goals of resolution, community building and safety. We might think of spheres of component parts, each consisting of those parts that contribute to particular goals.

The spheres and, through them, all the component parts of the Justice Network are coordinated and monitored by a Hub. The purpose of the Hub is to provide a framework for the dynamic interaction of the Justice Network’s component parts.

With this overview in mind, let us consider the structure of the Justice Network in more detail.

Component Parts

The building blocks of the Justice Network consist of more than just programs. They include programs, systems, processes, boards, committees, movements, efforts, organizations, agencies, funds, individuals and so forth. The restorativeness of the Justice Network is determined not only by the restorativeness of each individual element, but also by the entire constellation of programs and elements as they interact with each other. 4 There is significant diversity among these components. They vary across the following four dimensions.

Relationship to the Justice Network

We might think in terms of three categories of programs based on the degree of permanence that a program has with the Justice Network. “Independent” programs are completely independent of the Justice Network. They contribute to the restorativeness of society, but are typically uninvolved in the Justice Network because they: (1) are too informal, (2) don’t adhere to all restorative standards set by the Justice Network, (3) don’t want to be part of the Justice Network or (4) don’t routinely deal with criminal problems or disputes. An example of an independent program is a community self-help coalition addressing problems related to vacant properties in a neighborhood, which becomes involved for a time in resolving a series of arsons.

“Temporary” programs are temporarily present in the Justice Network. They may be permanent and well established as programs or organizations in their own right, but they have only a temporary presence within the Justice Network. An example of a temporary program is a church that provides reintegration services for an offender who is a member of their community.

“Fixed” programs have an ongoing presence in the Justice Network. They are established programs themselves, but also have established an ongoing relationship with the Justice Network. An example of a fixed program is an NGO that provides halfway-house beds for prisoners returning to the community.

Fixed programs further subdivide into: (a) those whose role is specific to criminal justice and thus operate only within the Network (like the halfway-house example) and (b) those that routinely operate both inside and outside the Network (such as a counseling or drug-treatment program).

Degree of Formality

Here, “informality” and “formality” refer to the degree of form or structure within a program. Informal programs may be completely spontaneous, lacking any chain of command, fixed order or tradition. Most informal programs are community-based, although there are exceptions. For example, the government acts informally when police spontaneously respond to a minor altercation by breaking it up and asking the participants to talk through their difficulties on the spot. Informal programs may occur in courts when judges work for completely new solutions to unusual situations. Informal programs may become connected to the Justice Network when they show stability in spite of their informality.

Formal programs are those with structured accountability, fixed order and tradition. A program sufficiently established to have an address in the phone book, an official name or any kind of advertising is considered more formal than an ad hoc committee of neighborhood residents, but less formal than the police force.

Relationship to Community and Government

The terms “community-based” and “government-based” refer to the location of the persons who are primarily responsible for running the program. Most programs include participation by both government and community members. Resolution- and community-building programs can be either community- or government-based. Many “safety” programs are government-based, but some are community-based as well (e.g., Neighborhood Watch programs).

Community-based programs receive government support, but depend heavily on the community for organization, funding and staffing.5 Most cooperative programs are community-based. Most free (see below) and informal programs are community-based. While community-based programs are relatively free from government control, they may be affiliated with government programs or supported by the government. Some community-based programs may originate as government-based and slowly be turned over to the community. The opposite process can also take place.

Government-based programs depend on the government for organization, funding and staffing. Most adjudicative programs are government-based. Government-based programs make a concerted effort to be informed by the community. They may also draw heavily upon community support.

Use of Coercion

The terms “voluntary” and “coercive” refer to the value of voluntary cooperation required. Resolution, community building and safety programs are more or less voluntary or coercive depending on the degree of willingness expected from the parties.

Voluntary programs depend on the willingness of the parties to participate. All cooperative processes are voluntary, while programs in adjudicative processes are made as voluntary as possible.

Coercive programs are those in which participation by one or more party is compelled. Most adjudicative processes are coercive, although cooperative elements can be introduced when appropriate.

It should be noted that “voluntariness” is an inexact term, and that persons may choose to participate in a cooperative process not because that is their desire, but because that is the best of the available alternatives.

Spheres

As mentioned previously, the Justice Network can be roughly divided into three general constellations or spheres of contributing parts, each addressing a different response to crime. These spheres are led, connected and monitored by the Hub.

1. The Resolution Sphere consists of the contributing parts involved in the claims and repairing the many kinds of harm (to direct and indirect victims, to directly and indirectly involved offenders, to their communities of care and to the community at large) that result from crime. It uses an inquisitorial approach to investigation of crime. It then guides parties into one of two processes for addressing the issues related to the crime. The cooperative process is used when the parties agree to work together to address the needs, claims and responsibilities arising out of the offense. This is considered the typical response to individual cases of crime. The adjudicative process is used as a safeguard when the parties choose to have an outside authority make decisions about resolving the crime, when the offender or the victim is uncooperative, the offender denies responsibility or the parties are unable to arrive at an agreement.

2. The Community Building Sphere is made up of the contributing parts that are available to assist victims in their recovery and offenders in their reintegration. It focuses on building respectful interaction within communities and teaching appropriate means of resolving conflicts and participating in difficult dialogues. This sphere also responds to systemic contributors to crime.

3. The Safety Sphere consists of the contributing parts that keep peace and order in the community.

The Community Building and Safety Spheres work together with the Resolution Sphere to provide safety, address needs and responsibilities related to crime and to prevent crime. Although those two spheres are made up of programs not always included in discussions of restorative justice, they are important to the ability of the Justice Network to accomplish its purposes. They must also conduct their work guided by restorative justice principles, values and goals.

The Hub

The Hub is the Justice Network’s coordination center and guardian of restorative justice principles values and goals. It provides oversight and leadership within the Justice Network in several ways. First, it offers strategic oversight of the Network as a whole. Second, it is responsible for operational leadership. Third, it refers individual cases and people to the appropriate parts of the Justice Network. Fourth, it ensures that community and government programs and elements receive training and assistance to perform their work well. Fifth, it monitors the Justice Network to assess and increase, as needed, the restorativeness of the Network as a whole and of its individual components. Finally, it provides administrative coordination within the Hub and the Network.

Community and government representatives6 make up the bodies that carry out the oversight and operational responsibilities. This assures that both have integral roles in Justice Network leadership and design. Referral mechanisms guide and follow cases from the moment they are reported by citizens, police or others as they proceed through the appropriate parts of the Justice Network. Training and assistance increases understanding of and participation in the Justice Network. Education efforts raise awareness of restorative justice values and give visibility to the work of the Justice Network with the goal of recruiting new programs and individuals to take part in the Justice Network. Finally, quality assurance—based on restorative values, community and program experience, and legal and human rights standards—helps maintain the high level of performance of programs and gives priority to ongoing improvement in practices.

Conclusion

This is a general overview of RJ CitySM and the balance of the working draft goes into much more significant detail. For the time being, this is available online at www.pficjr.org/programs/rjcity. Beginning in October 2007 it will be available at www.rjcity.org.

Endnotes

1. Executive Director, Centre for Justice and Reconciliation at Prison Fellowship International. This paper was adapted from a larger working document on RJ CitySM and presented on October 18, 2006, at the IIRP Conference “The Next Step: Developing Restorative Communities, Part 2,” held at Bethlehem, PA.

2. This campaign was organized after consultation with Ann Warner Roberts, who had been brought in as a consultant early in the coalition’s efforts. The following strategy was based on her recommendations to the coalition.

3. For exceptions to this, see the sections following on the use of coercion and force.

4. Throughout these documents, the terms “program,” “element” and “contributing part” will be used interchangeably and with the understanding that they refer to the many types of Justice Network building blocks.

5. This requires a significant reallocation of resources, including money, as the focus of crime prevention and intervention moves from government dominance to significantly expanded community control.

6. These representatives reflect the demographics of RJ CitySM and its communities.