Ted Wachtel's keynote from the 2011 European Congress on the Family Group Conference: Democratizing Help and Welfare in Utrecht, the Netherlands, October 19-21, 2011:

Restorative Practices: Creating a Unified Strategy for Democratizing Social Care, Education and Criminal Justice

I’d like to tell you about the first Family Group Conference story that I ever heard. I heard it in 1994 from an Australian police officer named Terry O’Connell. Terry was traveling around the world on a Winston Churchill Fellowship and he came to where I live in the U.S., in Pennsylvania. When he told this story I was deeply moved. It touched my heart. So much so that Terry said he remembered me because I was the person sitting in the front row with tears running down his cheeks.

Technically speaking, it’s not a Family Group Conference story. For several years Terry, and others like me who he influenced, used the wrong term. I even used the wrong term in Real Justice, my first book about conferencing. In later editions, I changed the term to “Restorative Conference.” So the first conference story that I heard employed Terry O’Connell’s adaptation of the Family Group Conference.

Terry had heard about New Zealand’s bold new experiment and he was inspired by it. He was running a community policing project in which he was trying to divert young offenders from going to court. So he used his imperfect understanding of the Family Group Conference to create his own intervention.

In O’Connell’s restorative conference there is no family private time. But he was determined to keep the professional, the facilitator, in this case the police officer, from interfering with the discussion between the people the conference brings together: the wrongdoers, the victims and their respective communities of care, family and friends. So he created a script for facilitators to read and they were supposed to keep to the script and not otherwise participate

The script consisted primarily of a series of open-ended questions which we now call the “restorative questions.” These questions are designed to give people an opportunity to speak freely without interference. The questions are used in the formal conference — but they also can be used informally — to create quick interpersonal exchanges between people — to help them gain a shared understanding of how everyone has been affected by an action or an incident.

The questions are helpful for parents, for teachers, for youth workers, for managers — for anyone in a position of authority who is responsible for managing behavior. We’ve had many people tell us that they carry the card in their wallet or purse, so they can readily access it.

On one side are questions that are asked of those who have caused harm:

- What happened?

- What were you thinking about at the time?

- What have you thought about since?

- Who has been affected by what you did?

- In what way?

- What do you think you need to do to make things right?

The second set of questions are asked of those who have suffered harm:

- What happened?

- What did you think when you realized what had happened?

- What impact has this incident had on you and others?

- What has been the hardest thing for you?

- What do you think needs to happen to make things right?

But I was going to tell you a story.

It’s a story about another Australian police officer who had just returned to his community after a conferencing training with Terry O’Connell. No sooner had he returned to his small rural town in the vast Australian outback, when he was presented with a youth crime. Four boys had seriously vandalized the interior of a building used as a meeting place by a local women’s organization. So he decided to use this crime as an opportunity to try out his new conference facilitator skills.

The rural community where he lived consisted of a small number of whites living among a larger number of blacks — most of whom lived on the aboriginal reserve set up by the Australian government. The four young vandals were all aboriginal and the members of the women’s group were all white.

So he invited and prepared all of those individuals for the conference: offenders, victims, and their respective families. To aboriginal people, family does not just mean mom and dad and siblings, but always includes extended family. And, with the dozen women in the organization and their families, the numbers for the conference became quite large. But there’s not a lot of rain in much of the Australian outback and the police officer could reliably count on holding the event outdoors, which he did.

He opened the conference by welcoming everyone and began to ask the boys the restorative questions, then the victims, their families and the boys’ families. Everyone had an opportunity to speak.

In the safety and the decorum of the conference, the boys spoke in a truthful and heartfelt way. What emerged from them, not as a justification or excuse, but in response to the question, “What were you thinking about at the time?” were the kinds of resentments that the boys held toward the more affluent white community, and reciprocally, the women talked honestly about their fears of living as a minority of whites amidst a larger aboriginal community. For the first time ever, the two disparate groups in this community had a genuine discussion and gained a shared understanding of each other. It was a very satisfying discussion. The outcome of the conference was that everyone was going work together the following weekend to repair the damage, side by side. What began as crime and a conflict, ended up being a beneficial community-building experience. And that touched me and everyone else listening to the story.

But now, here’s the surprise ending. The conference was not legal. The police officer had no authority, no legal jurisdiction to do what he did. The aboriginal boys were only 7, 8 and 9 years old. They were below the age of responsibility under Australian law.

But the police officer did the conference anyway, because he cared about his community and he was concerned about the negative effects of leaving the incident unresolved. And he had just learned the conferencing skills that he felt would help bring resolution to this issue.

I first learned about the ideas of Jürgen Habermas, the German sociologist and philosopher, from Frank Früchtel, who will be speaking to you, here, tomorrow morning. Frank spoke at an IIRP conference in Pennsylvania several years ago, and because he is quite knowledgeable about this topic, I will read you a few short excerpts from his paper.

“Habermas states that we have two options of explaining how society operates: the logic of the System or that of the Lifeworld. The lifeworld views society as a community: a network of relationships among people, such as family, friends, colleagues, schoolmates, lovers, club members and so forth. Members of such networks support each other because of the affinity and affection they experience in their relationships. They often will look out for each other and in times of need, help each other, simply because they care.”

“On the other hand, the system is modern society with its administration and laws, politics and economy, organisations and professionals — experts who use logic that is significantly different to the logic of the lifeworld.”

“The fabric of the lifeworld is woven by a type of communication where people try to understand the other person’s situation and viewpoint and act on the resultant understanding to affect each other. The more engaged people are with their lifeworld, the more they experience a sense of belonging and self-worth, receive and give support, and the more they integrate as members of a community.”

I’m sure that you can see why I would want to share the concept of Lifeworld after telling this story. And if you go to the website of my organization, the IIRP Graduate School, at the top of every webpage is our logo and the words that describe our efforts: “Restoring Community in a Disconnected World.” While I didn’t know about the concept of Lifeworld when I chose those words, it is now clear to me that Lifeworld provides a useful context — a shared vision — for managers, social workers, educators and criminal justice professionals, that moves us toward a more engaging and democratic way of working with our fellow human beings.

Now, I’d like to tell you about the first Family Group Conference story that I ever heard. This time I’m using the term properly. I was attending a professional conference in England where I heard a grandmother describe how terrified she was that social workers were going to place her grandchildren in foster care because her daughter, a single mother, was suffering from severe depression. The grandmother poignantly described her family’s feelings of helplessness and desperation in the face of the power of government, however well-intentioned, to sweep into their lives and take away the children that they loved so dearly.

All of a sudden the skies brightened when the grandmother and her extended family were offered an opportunity to participate in a family group conference. Grandparents and aunts and uncles and siblings all rallied around the struggling mother. They created a structured schedule of visitation and volunteer support at critical hours of the day that ensured the well-being of her children. The plan was sufficiently rigorous to satisfy the concerns that had brought about the threatened intervention by the social worker and the courts.

Here’s another story. It’s familiar one. A boy gets angry, curses at his teacher and she sends him to the administrator who suspends him from school for three days. This kind of occurrence is commonplace in schools today. We lament the lack of civility, the loss of behavioral boundaries, the irresponsible parents who have raised this child, and we explain the punishment as “holding the student accountable for his behavior.”

Accountable? How so? The punishment is passive. The student doesn’t have to do anything. He stays angry at the teacher and the administrator. He thinks he’s the victim. He doesn’t think about how he’s affected others or about how he might make things right. And he returns to the classroom with nothing resolved.

Nils Christie, the distinguished Norwegian criminologist, wrote a landmark essay entitled “Conflict as Property.” He argued that our conflicts belong to us and that courts and lawyers and other professionals steal our conflicts, taking away our opportunity to resolve them and robbing us of whatever benefits might come from that. Schools and administrators do the same. Both courts and schools miss a critical opportunity to engage people and to resolve the conflict with better results.

If the school administrator wanted to ensure that the angry student would return appropriately to that teacher’s classroom, he would organize a restorative conference to bring the offending student and his family together with the teacher and other students who were affected by the incident. Although it may surprise those unfamiliar with restorative conferences, such meetings almost always produce positive outcomes, allowing the student and teacher to restore their relationship and return amicably to the classroom.

Fundamental Hypothesis of Restorative Practices

The IIRP has proposed a unifying hypothesis for restorative practices. It’s very simple:

“Human beings are happier, more productive, more cooperative and more likely to make positive changes in their behavior when those in positions of authority do things with them, rather than to them or for them.”

There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that this is true. In criminal justice there have been studies showing that restorative justice decreases offending and reduces post-traumatic stress in victims. In education, restorative practices reduce violence, bullying, misbehavior in schools and consequently reduce suspensions and expulsions. And in social work, I’m sure I don’t have to tell this audience about the improvements in outcomes for young people and their families through family group conferences.

Those of us who are interested in reforming the System have been working in our own silos, in our own professions, using different terminology. Briefly click through and point out the terms. And that’s ok that we have different terms. Underlying these terms is a shared ethos, a more democratic way of working with people. So also we need to develop a shared terminology.

In my own organization, IIRP Graduate School, we have defined four continuing education programs based on this common framework. Each has its own website:

All four programs address different areas of endeavor, but all employ restorative practices and rely on the Fundamental Hypothesis.

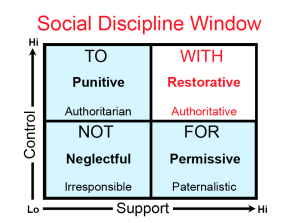

Social Discipline Window

I’d like to suggest another concept in a unifying framework: the social discipline window. All of us in positions of authority are responsible for enforcing certain boundaries of behavior: in our families, our schools, our organizations, our communities and our societies. We attempt to this in two ways, shown by two axes: control and support.

I’d like to suggest another concept in a unifying framework: the social discipline window. All of us in positions of authority are responsible for enforcing certain boundaries of behavior: in our families, our schools, our organizations, our communities and our societies. We attempt to this in two ways, shown by two axes: control and support.

So where does your own practice fall on the social discipline window? As a parent? As a professional? Briefly point out the terms each quadrant.

Of course, society has a responsibility to protect children and to also set boundaries on their behavior. Those of us who advocate the family group conference maintain both high control and high support at the same time. We are authoritative, but not authoritarian. We are responsible for setting limits, but we engage people in a participatory process which allows them a substantial say in those matters which they care about the most — the well-being of their children and families.

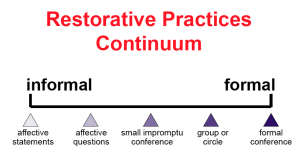

Restorative Practices Continuum

Here is still another element of a common framework: the restorative practices continuum.

I want to emphasize that restorative practices go beyond the formal conference processes. They can be informal and they can be proactive. We don’t have to wait until little aboriginal boys commit crimes. We can encourage people to appropriately express their feelings in their everyday life and we can have circles in families, in schools and in community meetings that provide a safe space for people to talk and listen to each other. The more opportunities that people have to communicate, the more “they experience a sense of belonging and self-worth, receive and give support, and the more they integrate as members of a community,” as Frank Früchtel pointed out. Through the continuum of restorative practices, we can enhance the role of the Lifeworld and diminish the role of the State.

John Braithwaite, the Australian criminologist, said: “The lived experience of modern democracy is alienation. The feeling is that elites run things, that we do not have a say in any meaningful sense.”

Voting and elections and legislatures seem most often to represent the interests of the rich and the powerful. And I don’t know how to solve that. But what would satisfy many people is simply to have a real say in the day-to-day problems that matter most to them and involve their families and friends and their immediate communities. Society would feel a whole lot more democratic if we were able to implement restorative practices across our schools and courts and social services.

So what stands in the way?

I was working on this speech the other day and I decided to take a break and go to the movies with my wife. We saw a new movie called “Moneyball.” It’s about American baseball and about a general manager of a baseball team, who comes up with a new way of doing things. But he meets with a lot of resistance and criticism. And at one point in movie he talks angrily about his critics — they don’t like change, don’t want to work differently, they feel threatened by the possible loss of their jobs or of their power. I felt his anger, because I recognized my own frustration and anger at those in schools and courts and social services and in leadership positions who oppose restorative practices — despite the growing evidence. They, too, don’t want to change and are threatened or frightened by engaging and empowering the people over whom they have authority.

You are the heroes of this movie we’re living in. You have new of way of doing things. You want to do them for the right reasons, not selfish reasons. But you meet with ignorance and conscious resistance. You are willing to go up against the forces of inertia, resistance, fear and doubt. But you don’t have to do it alone. There are other reformers in other field who share your values.

In the city of Hull, in the U.K. we have had a exciting opportunity to ultimately train 23,000 people across all professions, from education to policing, from youth justice to social work, to create the world’s first restorative city. This afternoon Estelle MacDonald, the director of the Hull Centre for Restorative Practice and I will be presenting a session about this project and its remarkable outcomes so far.

Over the 14 years that we have held our annual IIRP conferences, thousands of people from diverse backgrounds have come together under the umbrella of restorative practices to share a common vocabulary, celebrate our common purpose and report on our growing experience and success.

Joining together will allow us to have a more powerful impact — to move all of our practices into the mainstream. And as I have heard Rob Van Pagée suggest — let’s bring to an end the two hundred years of the interventionist state. Let’s build societies that favor the Lifeworld over the State, where people, in the midst of their caring communities, increasingly rely on Eigen Kracht, their own strength, their own power.