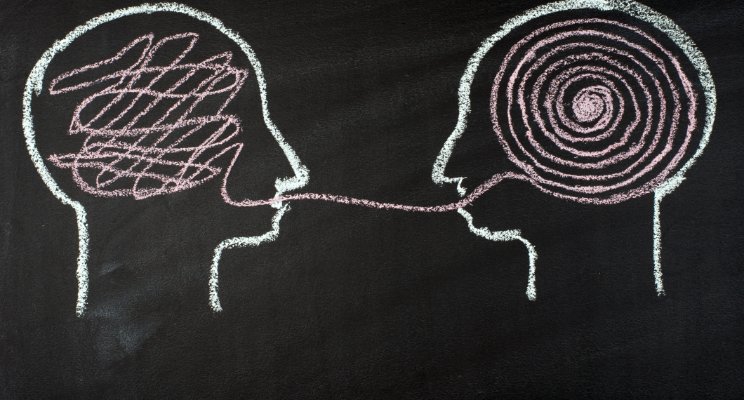

In Joseph Campbell’s seminal work, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, he discusses how life’s tragedies remind us of that which is fragile and life’s comedies remind us of that which is invincible within us and around us. It is only by grasping the reality of both aspects of our personal story that we come to know ourselves and to fully understand others. Even in restorative conferences held in the wake of serious offenses such as murder, victims who choose to participate commonly report that they came to see the offender as an imperfect and broken human being, instead of an all-powerful monster. More than any other method, humans use storytelling and voice to make sense of emotionally powerful experiences. A dignified life is one in which we feel that our story is heard, understood and matters to those around us.

When I first began working for the International Institute for Restorative Practices (IIRP), I was employed as an intern youth counselor at one of our day treatment alternative schools for at-risk teens. One of the unique aspects of the organizational cultural was something called “basic concepts,” to which all staff were required to adhere. These were regularly discussed and reviewed during monthly staff team-builders. They were group exercises designed to reinforce important organizational norms and ideas. Two of these basic concepts were:

We believe that others benefit from, and actually welcome, honest feedback.

If we have a legitimate concern about a fellow staff member’s behavior, we should present the concern to them directly or seek supervision.

Previous to the IIRP, I had worked in several settings that claimed to have a similar culture and norms, but failed to put them into practice in the daily life of the organization. Understandably, my reaction to these early team-builders and basic concepts was somewhat cynical.

Early in my employment, a colleague made me a target for harsh and embarrassing teasing, a form of workplace bullying that frequently embarrassed me in front of our staff and students. One day after a particularly troubling interaction, I asked to speak with the school supervisor. She listened to me patiently and expressed concern for what I had told her, saying, “I’m very sorry that this happened to you. You do not deserve to be treated like this and his behavior is not acceptable.” Then she asked me, “Would you like to tell him how his behavior is affecting you?” Surprised, I responded that I frankly thought this was her job! She told me that she would talk to him as well, but that I deserved the opportunity to confront him directly. Sensing my hesitation, she offered to join me and tell him together that this behavior needed to stop. I agreed. In this conversation, we used restorative questions as a guide:

What happened?

What were you thinking about at the time?

What have you thought about since?

Who has been affected and in what way?

What’s been the hardest thing for you?

What needs to happen in order to make things right?

I started by telling him that I was frustrated and angry with him and recounted several recent incidents when he had teased and embarrassed me. To my surprise, I also shared some of my own history with this type of behavior in the past. I told him that I grew up in a neighborhood where I faced fights, physical threats and bullying as a regular part of my childhood. I also shared that in my experience in the military, there were a few authority figures who regularly abused their power in this way – using their role as training leaders to physically and emotionally abuse their subordinates.

I grew surprisingly emotional during this part of the conversation. I had not planned on sharing anything about these parts of my life story, and I certainly didn’t foresee the emotions that rose in me. I then said that the hardest part of what happened wasn’t his behavior per se, but that I had been trying hard to trust that this organization was different from others I had experienced and that his behavior contradicted the values this organization claimed to uphold.

I related how difficult it was for me to trust authority figures and that I had been working to be more emotionally honest and open – especially in my desire to be more effective as a counselor and role-model for the youth we served. He was supposed to be mentoring and helping me, but instead he was hindering my professional development.

To my shock, he didn’t make excuses. He hung his head and admitted that this kind of behavior had been an ongoing problem for him, both at work and at home, and that this wasn’t the first time he had been confronted about it. He apologized and asked me what I needed from him.

I thanked him and told him that the teasing and bullying needed to stop immediately. I suggested that if he had a real criticism, he should talk to me privately first and not use sarcasm. I also asked that we update the other staff on our conversation and his commitments to change his behavior.

His behavior toward me changed for the better, and I never had the same issues with him again. This change was not because he was told he would be fired, or that he was formally reprimanded, or because of any aggressive response from me. He changed because by sharing our personal feelings and stories in a very real and human way, we both affirmed that we deserved better. I affirmed my dignity by insisting that I not be treated that way. His dignity was affirmed by me, and the organization, by setting strong limits and high expectations for his behavior.

Simply put, we told him that he was a better person than his behavior suggested. We held him accountable while affirming his worth as a person and his potential to change. Ultimately, he did make a choice to leave the organization and did so with a truly warm and heartfelt farewell.

He acknowledged that this was not the place for him, but that he had learned a lot about himself during his time with us.

One of the great contributions of restorative practices as a field involves bringing to full consciousness the way personal narratives impact our daily lives, relationships and work. Research into adult learners in programs utilizing restorative practices even found that sharing personal narratives helped to reconcile past conflicts, hardships, and trauma.

Each of us is unrepeatable and unique. As such, our personal narratives contain the seed of our dignity as individuals. Sharing those stories in the presence of others builds a more thorough understanding of our own lives and the humanity of those with whom we live and work.