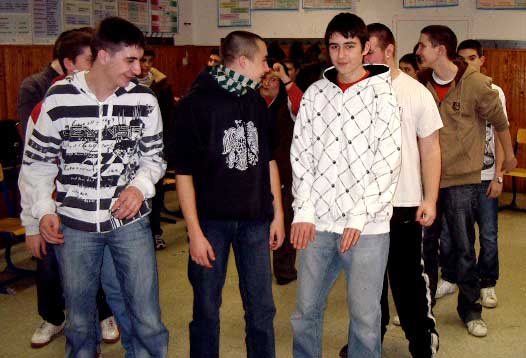

Hungarian high school students participate in a restorative exercise, forming a “boat” and “rowing” into the future, with their teacher at the center.In April 2010 Vidia Negrea, director of Community Service Foundation (CSF) Hungary, provided an introductory training in facilitating restorative conferences for four different youth group homes in Budapest. This is just the latest development in her work spreading restorative practices in Hungary, which also includes major efforts in schools and prisons.

Hungarian high school students participate in a restorative exercise, forming a “boat” and “rowing” into the future, with their teacher at the center.In April 2010 Vidia Negrea, director of Community Service Foundation (CSF) Hungary, provided an introductory training in facilitating restorative conferences for four different youth group homes in Budapest. This is just the latest development in her work spreading restorative practices in Hungary, which also includes major efforts in schools and prisons.

Psychologist Negrea came to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA, in 2000 to learn about restorative practices and has never looked back. (See: www.iirp.edu/article_detail.php?article_id=NDUw, www.iirp.edu/article_detail.php?article_id=NDM0 and www.iirp.edu/article_detail.php?article_id=NTk1 for three articles which give a history of Negrea’s work bringing restorative practices to Hungary.)

Her recent work has been supported by the Ministry of Justice Hungary and the city of Budapest, including a project to reduce aggressive behavior in children and youth, which is bringing restorative practices to six big-city high schools.

At first some of the leaders in these high schools weren’t open to the idea of restorative practices. The success of the practices in the wake of one particular incident changed their minds.

A group of students who had previously gone to different lower schools and now attended the same high school were traveling together on the Metro (subway) to vocational school, when one of them came up with a hazing dare: Everyone had to push someone in front of an oncoming train and then pull them out of the way at the last minute.

When Negrea visited the high school the boys attend, it seemed to her to be in bad shape. Dissatisfaction permeated the entire school community. Student misbehavior was very common. The teachers barely knew each other and provided no mutual support; instead they just complained about the students and the administration. Negrea was given four weeks, one and a half hours per week, to help address the problem. Instead of tackling the hazing incident directly, she decided first to build a sense of community among staff members and between staff and students.

She started with games and feedback exercises. By the third week the students were really involved in the process and had begun putting their chairs into a circle in preparation for the activities themselves. One skeptical teacher sat outside the circle for a couple of weeks, but even she put aside her cynicism when she saw how eager the students were to share their feelings with the rest of the group. By the third week she joined the circle.

That week one of the students gave her feedback, telling her that when she went on talking in class after it was over, he felt frustrated because he had no break between classes and no time to go to the bathroom. The surprised teacher thanked the student for his honesty and the courteous way he had shared it.

The teacher, who was about to retire, was now finally enjoying being in school, thanks to the positive feelings the circles had generated in her class. She decided to try to show the students how she felt by playing a game. Using no words, she directed all the boys in the class to stand in the shape of a big boat, in which they all rowed together. Then she stood in the middle of the “boat” and shouted, with all her heart: “Stroke! Stroke! We’ve got to get to land, no matter what! Don’t give up! I’ll help you!” The boys laughed, surprised at this new behavior from their formerly staid and sour teacher. Now there was a real feeling of community in this classroom.

When the school principal saw a photo of that game, he asked Negrea: “What do you need to implement this program?” In the next session the class decided to develop a plan as a group — students and teachers together — on how to move forward in the future. The plan included regular circles every week, with teachers, students and the children and youth coordinator, as well as a parent night. During the parent night they wanted to ask the restorative questions around the Metro incident: What happened? What were you thinking about at the time? What have you thought about since? What do you think needs to be done to make things right? Who has been affected by what you have done and in what way?

On parents’ night, the students presented the restorative circle process to the parents, but they immediately wanted to blame and punish the students. They also wanted a teacher to accompany the students on the Metro from then on. The students replied that this wasn’t the point: They had learned to control themselves, they maintained. They made an agreement to report on their Metro trip to vocational school every week.

For a month, the students had no trouble on the Metro. At this point it was decided that the whole school should learn about the way the Metro problem had been resolved. This successful resolution then filtered up to the top of the Budapest school district administration. Thus wider implementation of restorative practices began in Budapest’s schools.

By April 2010 the first four schools to implement the practices have given very good feedback on the process, although there are no hard data yet. April’s elections in Hungary brought in a new national administration, so it remains to be seen whether the government will continue to fund restorative practices in schools. However, said Negrea, they’re not going to wait for government money but will find other funding sources.

In the SOS Children’s Village for seriously at-risk youth (age 14 to 21) including orphans and sex abuse and incest victims, restorative practices have really become part of the culture since implementation began in 2005. They’ve done fantastic work, said Negrea. Kids and staff are taking responsibility for issues as a group and a strong community feeling prevails.

On the criminal justice front, Negrea helped train 80 probation officers in family group decision making (FGDM), which brings together extended family and friends to help resolve issues. After two years more than half of these probation officers are still using FGDM in prison and parole and are expanding its use in many ways. (Click here for an article on how FGDM is being used to help prisoners reintegrate into society, in both the U.S. and in Hungary.) In June 2010 probation officers from every region in Hungary will present results of their experiences with FGDM at a national conference.

Negrea is also participating in a prison program in partnership with the Sycamore Tree Project of Prison Fellowship International (www.pfi.org/cjr/stp). She was asked to observe 12 prisoners — all serious criminals — who wrote letters of apology to their victims. She plans to take this further with a multi-step approach: First they will hold FGDM conferences with the prisoners and their family members to restore relationships and develop a plan for the prisoners’ futures. Then they will try to expand on the prisoners’ letters of apology, hoping they will lead to restorative conferences between the prisoners and those they have harmed.

Again in partnership with the Sycamore Tree Project, Negrea has been overseeing a case in one of the prisons where she trained probation officers. A prisoner who was sentenced to 13 years for murder is about to be released after 11 years. In September 2009 an FGDM was held with his family to make a plan for a December five-day home visit. Everyone followed the plan, and the visit went very well, both with the prisoner’s family and with the people in his village. In June 2010 Negrea will facilitate another FGDM conference involving the prisoner’s family members and people from the village to make a plan for his release from prison.

The Ministry of Justice is enthusiastic about FGDM, as are supervising probation officers and criminologists from all over the country. What’s more, when Hungary is in charge of the European Union in 2011, Negrea hopes that FGDM can be developed as a model probation and parole tool for all of Europe.