An introduction to restorative practices, the underlying philosophy of SaferSanerSchools, by Ted Wachtel, President, International Institute for Restorative Practices, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Adapted from paper presented at the “Reshaping Australian Institutions Conference: Restorative Justice and Civil Society,” The Australian National University, Canberra, February 16-18, 1999. Also available as Adobe Acrobat (".pdf") file. (Size 29K)

Adapted from “Restorative Justice in Everyday Life: Beyond the Formal Ritual,” a paper presented at the “Reshaping Australian Institutions Conference: Restorative Justice and Civil Society,” The Australian National University, Canberra, February 16-18, 1999.

Punitive-Permissive Continuum

Punishment is the normal response to misbehavior, wrongdoing and crime in families, schools, workplaces and the criminal justice system. Those who fail to punish naughty children and offending youths and adults are often labelled “permissive.”

The punitive-permissive continuum (Figure 1) reflects this limited perspective and its confining implications for teachers and school administrators. They can only choose whether to punish or not to punish and the severity of the punishment—how many detentions or how many days of suspension.

As part of an overall societal trend, schools in the United States and other countries have become increasingly punitive, suspending and expelling more students than ever before. In part, that has resulted from more and more difficult and violent behavior on the part of students and, in part, because more and more schools have adopted strict “zero tolerance” policies which limit the discretion of school administrators. Not wanting to be perceived by the public as permissive, schools have moved toward the extremely punitive end of the continuum.

Loss of Relationships and Community

The increasingly difficult and violent behavior among school students and related punitive school climate are both products of the alienation and loss of community that plagues modern society in general. Throughout human history and until recently, human beings have lived among their extended families in homogenous neighborhoods where all of the parents served as collective parents to all of the children. Anyone in the neighborhood could discipline anyone else’s children because everyone shared the same basic values.

Now that has changed, especially in America, where people readily move from one coast to the other, leaving behind their established relationships. Not only do aunts and uncles and grandparents and cousins find themselves scattered across the continent, but nuclear families find themselves split and scattered. Pieces of nuclear families often live alone or join with pieces of other nuclear families, trying to form a new whole. Even in intact nuclear families economic demands have caused both parents to work. Consequently parents have less time available for their relationships with their children and extended families.

The world is changing at a breathtaking pace. Seemingly without hesitation, we have systematically altered or destroyed the social patterns that have characterized human life as long as there has been human life.

We wonder about the growing violence and rudeness and anger in our society. We seem to place disproportionate emphasis on influences like violence on television or video games or the internet or changing sexual values or lower academic standards. However, such issues are relatively insignificant when compared to the deterioration of family and community—the basic building blocks of human society.

We are stuck in a vicious circle. The loss of relationships and community negatively impacts students and their behavior, which in turn fosters a more punitive school environment, which further exacerbates relationships between young people and adults. John Braithwaite, the well-known Australian criminologist, has described how punishment stigmatizes offenders, fostering negative subcultures. Growing numbers of young people do not feel connected to mainstream society and its values.

Punitive school policies undo the bonds between educators and students, but they also alienate parents from educators. Even responsible, caring parents are struggling against the same deteriorating social norms schools face in dealing with young people. Harsh and arbitrary penalties imposed on their children make parents feel helpless, shamed, blamed and isolated.

Punishment has not proved effective in stopping rude and challenging behavior from becoming commonplace in schools where such behavior was once a rarity. Educators everywhere face a growing number of young people who are willing to go beyond the beyond, behaving outrageously even when faced with repeated penalties and exclusion. But because punishment is seen as the only way to hold students accountable for their behavior, we as educators often feel trapped on a one-way street leading to a dead end.

Holding Students Accountable

Our society’s fundamental assumption is that punishment holds offenders accountable. However, for an offending student punishment is a passive experience, demanding little or no participation. While the teacher or administrator scolds, lectures and imposes the punishment, the student remains silent, resents the authority figure, feels angry and perceives himself as the victim. The student does not think about the real victims of his offense or the other individuals who have been adversely affected by his actions. So, are we holding the student accountable?

Doing things to an offending student merely alienates him. We must do things with him. We must engage him in an active way to truly hold him accountable. Simultaneously, we want to build positive relationships between the student and those affected by his behavior.

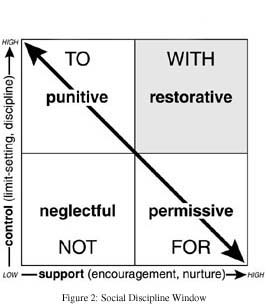

Social Discipline Window

We need a more useful way of looking at school discipline and social discipline than the limited punitive-permissive continuum—to punish or not to punish. We need to look through a social discipline window comprised of both control and support (Figure 2). We define “control” as discipline or limit-setting and “support” as encouragement or nurturing. Now we can combine a high or low level of control with a high or low level of support to identify four general approaches to social discipline: neglectful, permissive, punitive and restorative (Wachtel and McCold, 2000).

We can subsume the traditional punitive-permissive continuum within this more inclusive framework. The permissive approach (lower right of Figure 2) is comprised of low control and high support, a scarcity of limit-setting and an abundance of nurturing. Opposite permissive (upper left of Figure 2) is the punitive approach, high on control and low on support. The third approach, when there is an absence of both limit-setting and nurturing, is neglectful (lower left of Figure 2).

The fourth possibility is restorative (upper right of Figure 2). Employing both high control and high support, the restorative approach confronts and disapproves of wrongdoing while supporting and valuing the intrinsic worth of the student who has committed the wrong.

In using the term “control” we are advocating high control of wrongdoing, not control of human beings in general. We want to free people from the kind of control that wrongdoers impose on them.

This social discipline window can also be used to represent parenting styles. For example, there are neglectful parents who are absent or abusive and permissive parents who are ineffectual or enabling. The term “authoritarian” has been used to describe the punitive parent while the restorative parent has been called “authoritative.” Research has found the authoritative (restorative) style of parenting to be most effective (Baumrind, 1989).

A few key words—NOT, FOR, TO and WITH—were recently identified as a shorthand method to help clarify these approaches for the staff at the Community Service Foundation’s and Buxmont Academy’s schools and group homes in southeastern Pennsylvania. (CSF and Buxmont are the two sponsoring agencies for Real Justice® and SaferSanerSchools™ which both provide training internationally in restorative practices.) If staff members were neglectful toward the troubled youth in the agencies’ programs, they would NOT do anything in response to their inappropriate behavior. If permissive, staff members would do everything FOR the youth and ask little in return. If punitive, the staff would respond by doing things TO them. But responding in a restorative manner, staff members do things WITH the young people in their care and involve them directly in the process. A critical element of this restorative approach is that, whenever possible, WITH also includes victims, family, friends and community—those in the school, group home or wider community who have been affected by the offender’s behavior.

Formal Restorative Practices

The restorative approach to social discipline expands our options beyond the traditional punitive-permissive continuum, initially the implementation of restorative practices in the criminal justice system and in schools was limited to formal processes like peer mediation or family group conferences (often simply called conferencing), the latter having been widely introduced to schools by the international Real Justice® organization.

A formal conference brings together offending students, their victims, and family and friends of the students or their victims—although there may be no overt victims depending on the nature of the offense. The conference facilitator convenes the conference and, using a set of scripted questions, helps the group explore how everyone has been affected and how the harm might best be repaired.

While peer mediation assists students in resolving conflicts with one another and conferences are very useful in handling major incidents of wrongdoing, we now realize a restorative school climate requires more than just formal restorative processes like conferencing. We will need to employ informal restorative practices as well—integrated systematically as part of everyday school life.

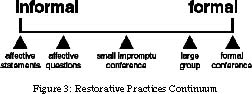

Restorative Practices Continuum

The regular use of restorative practices is what has produced remarkable cooperation and positive behavior among the delinquent and at-risk youths who have been placed at CSF/Buxmont’s schools by juvenile courts or public schools. As Terry O’Connell, the Australian police officer who pioneered the scripted version of conferencing, remarked when he first visited a CSF/Buxmont school in 1995, “You are running a conference all day long.” At that time we had never used formal conferences nor had we heard of the term “restorative.” But now we recognize we have created a school climate characterized by the everyday use of a wide range of informal and formal restorative practices.

The term “restorative practice” includes any response to wrongdoing which falls within the parameters defined by our social discipline window as both supportive and limit-setting. Once we examine the possibilities, we see they are virtually unlimited. To illustrate, I will offer some examples from everyday life at our schools and group homes and place them along the restorative practices continuum (Figure 3).

Moving from the left end of the continuum to the right, the restorative interventions become increasingly formal, involve more people, more planning, more time, are more complete in dealing with the offense, more structured, and due to all of those factors, may have more impact on the offender.

On the far left of the continuum is a simple affective response in which a teacher responds to misbehavior by letting the offending student know how he or she feels about the incident or misbehavior. Instead of saying, “Jason, how many times have I told you not to do that?” or handing out a punishment, the teacher might take Jason aside after class and say, “Jason, you really hurt my feelings when you act like that. And it surprises me, because I don’t think you want to hurt anyone on purpose.” And that’s all. If a similar behavior happens again, we might repeat the response or try a variation, perhaps asking, “How do you think Mark felt when you did that?” and then waiting patiently for an answer.

By simply expressing our feelings to misbehaving students we come to realize they typically don’t have a clue as to how their behavior has affected others. Most young people are very self-absorbed. They are genuinely surprised to find out how they have affected a teacher and as a result, they begin to see their teachers as fellow human beings, not just as those adults who give them a hard time. The change in their relationship with their teacher is sometimes dramatic and almost always meaningful.

In the middle of the restorative practices continuum is the small impromptu conference. I was with CSF’s residential program director, awaiting a court hearing about placing a 14-year-old boy in one of our group homes. His grandmother told us how on Christmas Eve, several days before, he had gone over to a cousin’s house without permission and without letting her know. He did not come back until the next morning, just barely in time for them to catch a bus to her sister’s house for Christmas dinner. The program director got the grandmother talking about how that incident had affected her and how worried she was about her grandson. The boy was surprised by how deeply his behavior had affected his grandmother. He readily apologized.

Close to the far right of the continuum is a larger, more formal group process, still short of the formal conference. Two boys got into a fistfight recently, an unusual event at our schools. After the fight was stopped, their parents were called to come and pick them up. If the boys wanted to return to our school, each boy had to phone and ask for an opportunity to convince the staff and his fellow students that he should be allowed back. Both boys called and came to school. One refused to take responsibility and had a defiant attitude. He was not re-admitted. The other was humble, even tearful. He listened attentively while staff and students told him how he had affected them, willingly took responsibility for his behavior, and got a lot of compliments about how he handled the meeting. He was re-admitted and no further action was taken. The other boy was put in the juvenile detention center by his probation officer. Ideally, he will be a candidate for a formal conference.

We can create informal restorative interventions simply by asking offenders questions from the script used by the facilitator in a formal conference: “What happened?” “What were you thinking about at the time?” “Who do you think has been affected?” “How have they been affected?” Whenever possible, we provide those who have been affected with an opportunity to express their feelings to the offenders. The cumulative result of all of this affective exchange in a school is far more productive than lecturing, scolding, threatening or handing out detentions, suspensions and expulsions. CSF/Buxmont teachers tell us classroom decorum in our schools for troubled youth is usually better than in the local public schools. But interestingly, at CSF/Buxmont schools we rarely hold formal conferences. We have found that the more we rely on informal restorative practices in everyday life, the less we need formal restorative rituals.

Effective Restorative Practices

To be effective in challenging and changing inappropriate student behavior, we have found several fundamental elements of good restorative practice.

1. Foster awareness. In the most basic intervention we may simply ask the offending student a few questions to foster awareness of how others have been affected by the wrongdoing. Or we may express our own feelings to the student. In more elaborate interventions we provide an opportunity for others to express their feelings to the student.

2. Avoid scolding or lecturing. When students are exposed to other people’s feelings and discover how victims and others have been affected by their behavior, they feel empathy for others. When scolded or lectured, they react defensively. They see themselves as victims and are distracted from noticing other people’s feelings.

3. Involve students actively. All too often we try to hold students accountable by simply doling out punishment. But in a punitive intervention, students are completely passive. They just sit quietly and act like victims. In a restorative intervention, students are usually asked to speak. They face and listen to victims and others they have affected. They help decide how to repair the harm and must then keep their commitments. Students have an active role in a restorative process and are truly held accountable.

4. Accept ambiguity. Sometimes, as in a fight between two people, fault is unclear. In those cases we may have to accept ambiguity. Privately, before the conference, we encourage individuals to take as much responsibility as possible for their part in the conflict. Even when students do not fully accept responsibility, victims or others who have been affected often want to proceed. As long as everyone is fully informed of the ambiguous situation in advance, the decision to proceed with a restorative intervention belongs to the participants.

5. Separate the deed from the doer. In an informal intervention, either privately with the students only or publicly, we may express that we assume that the students did not mean to harm anyone or that we are surprised that they would do something like that. When appropriate, we may want to cite some of their virtues or accomplishments. We want to signal that we recognize the students’ worth and disapprove only of their wrongdoing.

6. See every instance of wrongdoing and conflict as an opportunity for learning. We are educators. We know that many of our students have a lot to learn about appropriate behavior and social norms. We can merely punish and alienate them, or we can see school problems and incidents as an opportunity to teach students what they sorely need to know. Teachers, guidance counselors, custodians, clerical staff and administrators, using restorative practices, can turn negative incidents into constructive events—building empathy and a sense of community.

Restorative Practices in Personal Life

For most of us working with restorative practices, we have found that they are contagious, spreading from our workplace to our homes. A new staff member at CSF/Buxmont recently told me how she, her husband and her younger son restoratively confronted her young adult son, who had just entered the world of work. They told him how annoyed they were with his failure to get himself up on time in the morning. Mom and dad expressed their embarrassment that their son had been late to work at a company where they knew a lot of his co-workers. They insisted they were stepping back. If their son lost his job, it was not their problem, but his. As a result of the informal family group conference, the young man now sets three alarm clocks and gets to work on time.

A police officer who was trained in conferencing shared how he confronted his little boy, who had torn off a piece of new wallpaper and at first denied doing so. The father used questions from the conference script. The youngster quickly stopped denying and became very remorseful and acknowledged that he had hurt his mother, who loved the new wallpaper, and the workman he had watched put up the new wallpaper. Dad felt satisfied that the intervention was far more effective than an old-fashioned scolding or punishment.

Restorative Practices in Professional Life

Restorative practice is a philosophy, not a model, and ought to guide the way people act in all of their dealings. In that spirit CSF/Buxmont agencies use restorative practices in dealing with their own staff issues, creating an atmosphere in which staff can comfortably express concerns and criticisms directly to supervisors.

Last year several employees became engaged in a squabble that was disrupting the workplace, so a conference was convened. In this conference there was no clearly identified wrongdoer. Rather, when the participants were invited to the conference, they were each asked to take as much responsibility as possible for their part in the problem and were assured that everyone else was being asked to do the same. There was a lot of self-disclosure and honesty in the preliminary discussion with each participant, so the facilitator felt confident that the conference would go well. Not only did a great deal of healing taking place during the conference, but several individuals made plans to get together one-to-one to further resolve their differences. The conflict is now ancient history and no longer a factor in the workplace.

Restoring Relationships and Community

By encouraging people to express their feelings, restorative practices build better relationships. Restorative practices demonstrate the fundamental hypothesis of the late psychologist Silvan S. Tomkins’s affect theory—that the healthiest environment for human beings is one in which there is free expression of affect, minimizing the negative, maximizing the positive, but allowing people free expression (Nathanson, 1992). From the simple affective statement to the formal conference, this is exactly what restorative practices are designed to do.

When an entire classroom or school runs on restorative practices the growth and enhancement of individual relationships cumulatively fosters a sense of community. A healthy community. A community in which teachers, administrators, parents and students pay attention to each other’s feelings and demonstrate empathy for one another. A community in which young people are held accountable while being supported, where they learn appropriate behavior without stigmatization.

Based on Direct Experience

Although readers might be understandably skeptical, the CSF/Buxmont experience is not theoretical or merely hopeful. The organization’s schools handle, at any one time, up to 300 of the more troublesome youth from juvenile courts and schools from four southeastern Pennsylvania counties. By bringing them together there is the potential for a very negative and challenging environment. However, thanks to the systematic use of restorative practices, most of the young people change their behaviors, cooperate, take positive leadership roles and confront each other about inappropriate behavior, at least during the time they are with us.

Restorative Culture Change

Having trained thousands of people in conferencing, Real Justice trainers have found that many trainees never actually conduct conferences. Some hesitate to facilitate a formal conference because they are afraid. Many do not have the authority to bypass existing procedures and sanctions, like zero tolerance policies in schools. So a large number of people, rather than running formal conferences, have implemented restorative practices informally. Similarly the SaferSanerSchools trainers have found that teachers may implement restorative practices in their classrooms, while their school administrators continue using exclusively punitive strategies. Or school administrators are uncomfortable challenging punitive school board policies, so they use restorative practices only with minor incidents.

We all know the world will change slowly and imperfectly. We cannot afford to be unrealistic or utopian. We must be flexible and experimental. We must avoid rigid boundaries and expectations. We must move beyond the limited framework of the formal ritual and recognize the wider possibilities, encouraging everyone to use restorative practices freely in their work and their daily lives.

Ultimately schools must become innately restorative because they cannot hope to effect meaningful change by merely employing an occasional restorative intervention. Restorative practices must be systemic, not situational. You can’t just have a few people running conferences and everybody else doing business as usual. You can’t be restorative with students but retributive with faculty. You can’t have punitive administrators and restorative teachers. To reduce the growing negative subculture among youth, to prevent outrageous behavior and violence and to restore relationships and community, restorative practices must be more than occasional tools. Restorative practice must become a whole new mindset, a way of looking at the world that changes our everyday lives and our behaviors.

References

Baumrind, D. (1989) “Teenagers reap broad benefits from ‘authoritative’ parents.” As reported by B. Bower in Science News, Aug. 19, 1989.

Braithwaite, J. (1989) Crime, Shame and Reintegration. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Nathanson, D.L. (1992) Shame and Pride: Affect, Sex, and the Birth of the Self. W.W. Norton and Company, New York.

Wachtel, T. & McCo l d , P. (2000) “Restorative Justice in Everyday Life.” In J. Braithwaite & H. Strang (eds.), Restorative Justice in Civil Society (pp. 117-125). New York: Cambridge University Press.