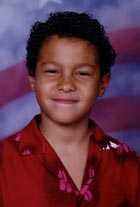

Honor student and second-degree black belt in karate Gino LeeFamily group decision making (FGDM, also known as family group conferencing or FGC) has made a big difference in the lives of many families. The story of how FGDM helped one family in Los Angeles County, California, USA, is a textbook example of just how powerful the FGDM process can be. FGDM helped this family ensure the well-being of a child who had fallen through the cracks of the child welfare system. Through an FGDM conference, the child’s extended family was empowered to make a plan for him, and this once troubled boy is now thriving and happy, living with his birth parents.

Honor student and second-degree black belt in karate Gino LeeFamily group decision making (FGDM, also known as family group conferencing or FGC) has made a big difference in the lives of many families. The story of how FGDM helped one family in Los Angeles County, California, USA, is a textbook example of just how powerful the FGDM process can be. FGDM helped this family ensure the well-being of a child who had fallen through the cracks of the child welfare system. Through an FGDM conference, the child’s extended family was empowered to make a plan for him, and this once troubled boy is now thriving and happy, living with his birth parents.

Not long after Gino Lee was born, his mother, Gina, had a nervous breakdown, and his father, Carl, took her to the hospital. Afraid that Gina might pose a threat to her child, the hospital staff contacted the Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS).

Because Gina was ill, Carl had already enlisted the help of family members, including his sisters and daughter, to care for Gino. “The whole family was helping out,” said Carl. But after Gina was hospitalized, unbeknownst to Carl, DCFS had been unsuccessfully trying to locate Gino at Carl’s home and had posted a note on his door indicating that if he didn’t contact them he would be arrested.

Carl called DCFS immediately and a DCFS worker met him at his daughter’s house, where Gino, then 40 days old, happened to be that day. Finding Gino safe and well fed, the worker decided that the boy should stay where he was. Carl didn’t know it at the time, but his son had just been officially “placed” by DCFS.

| The Los Angeles County Family Group Decision Making (FGDM) Program has conducted hundreds of family conferences in support of children and families. To learn more about the program, click here. To read an article in the Los Angeles Daily News about the program, click here. |

Carl tried to take Gino home, but DCFS wouldn’t allow it, so he went to court to straighten the matter out. The DCFS report to the judge asserted that Carl was on drugs and in rehabilitation, and that Gina was on drugs and in a gang. Said Carl in an interview, “I said, ‘Wait a minute, where’d all this stuff come from?’” The DCFS worker had deduced that Carl was on drugs, because, Carl said, “She said I had red eyes.” Gina was in day treatment and on medication, having her blood drawn frequently to monitor the dosage. Hospital staff testified to that effect and confirmed that Gina could not have been using narcotics. Added Carl, “Gina had never been arrested for anything in her life. So how could they say that she was in a gang?” Nevertheless, the judge continued the case for six months, so Carl was not allowed to take Gino home.

Six months later Carl returned to court to bring him home. His daughter was “a marvelous parent, an excellent caregiver,” said Carl, but Gino was his son and he wanted him home.

Carl told the judge that before DCFS became involved he had already enlisted his family’s help in raising Gino and that they didn’t need children’s services. But, said Carl, “Once they get you in that system, they don’t want to change it.” The judge continued the case for six more months. This scenario was repeated six times over the next three years.

Then Carl’s daughter became involved with a new man who began abusing her, her own children and Gino, too. When the abuse surfaced, DCFS sent the children to foster homes.

Carl and Gino

Carl and Gino Gina and GinoWhen Gino was returned to Carl’s daughter’s home, Carl, who saw Gino on weekends and took him to school on weekdays, noted that Gino was still being abused. He felt he had no choice but to report his daughter to DCFS. Naturally, this caused conflict between Carl and her, and DCFS did nothing to stop the abuse. So Carl filed a petition for custody of Gino. The petition was denied.

Gina and GinoWhen Gino was returned to Carl’s daughter’s home, Carl, who saw Gino on weekends and took him to school on weekdays, noted that Gino was still being abused. He felt he had no choice but to report his daughter to DCFS. Naturally, this caused conflict between Carl and her, and DCFS did nothing to stop the abuse. So Carl filed a petition for custody of Gino. The petition was denied.

One day, another little boy hit Gino in the head with a skateboard. When Carl called DCFS and asked what they were going to do about it, he was told, “Children do things like that to other children.” “But parents are supposed to stop kids from doing stuff like that right away,” said Carl, who filed another petition to change Gino’s placement. This time the court stopped all of Carl’s visitation rights with Gino for three months.

Carl filed an appeal: “All I was trying to do was stop him from getting hurt,” he said, “Make them do what they said they were going to do: ‘Children’s Protective Services.’”

A year passed before the appellate court heard the case. Carl won the appeal, and the appellate court judge wrote a reprimand to the children’s court judge that said “any judge should have known to remove the child right away.” The children’s court judge set the appeal aside and told Carl and Gina to return to court in 30 days.

The children’s court judge also ordered that Gino receive counseling, as he had been diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder. He had failed kindergarten and was, said Carl, “an emotional mess.” Carl had to appear at a special hearing, because he had told his son that Gina was his real mother. DCFS said that he should have let a counselor do it.

Several days later, Carl got a phone call informing him that Gino was in the hospital, following an accident. DCFS denied Carl and Gina permission to visit him. “Nobody would tell us what happened to him,” he said.

When Carl and Gina returned to court (earlier than the 30 days decreed by the judge, because of Gino’s “accident”), they learned that he had been thrown into a wall face first “with such an impact that his face knocked a hole in the wall,” said Carl.

At this point, “even though there was no question of abuse on my part or Gina’s part, the judge ordered us to go to parenting school and anger management school and to get a drug evaluation, rather than doing anything to stabilize where he should be living,” said Carl. Despite the fact that the appellate court ruling had been in their favor, granting them unmonitored visits, phone calls and overnight visits, the children’s court judge changed this to monitored one-hour visits and 15-minute phone calls.

When Carl tried to protest, he said, the judge told him: “‘If you say one more word, I’m going to place him up for adoption and let him get lost in the system.’ And I said to myself, this judge has the power of God. She’s emotionally executing my child.”

Gino was placed in a foster home in another county—illegally—said Carl. The home had no other children and no toys, having never had children before. Carl took some toys to the foster care agency for Gino but was instructed not to.

“You don’t have the slightest idea what a parent goes through when he’s dealing with this,” said Carl. Hoping to learn how to save his son, he attended DCFS parenting school. “They told me if there was something that was going wrong to consult with the social worker, then the supervisor, then my attorney, then the attorney’s firm, then make a written request to the judge, then file an appeal,” he said. “I followed that down to the finest detail.”

Carl filed five petitions and an appeal to save his son, to no avail. He was required to submit to numerous random drug and alcohol tests, all of which he passed. Years later, Carl learned the reason for the tests: His initial DCFS evaluation had contained the misinformation that he had once been in rehabilitation for drugs and alcohol; he had actually been in rehabilitation for a work-related injury. Then one day, Carl got a call from Joselyn Geaga-Rosenthal, director for family group decision making (FGDM) in Los Angeles County, asking if he’d like to try a new program that could help get his son out of foster care. “You’ve got a program that’ll get my son out of the foster home?” asked Carl. “Yeah, I’ll try it!”

| The IIRP, in partnership with American Humane’s National Center on Family Group Decision Making, has produced a video about FGDM, Family Voices, featuring families speaking about their experiences with FGDM. Carl Lee appears in this video. To learn more about the video, click here. |

Following FGDM procedure, Joselyn contacted everyone in Carl and Gina’s extended families to attend a conference to decide on the best course of action for Gino. “Gina’s got about a billion people in her family, and she called all of them,” said Carl. Everyone agreed to come, even family members who had never met Gino.Said Joselyn, “The daughter was the one referred [for an FGDM], because she was being ‘intransigent’ from our perspective. But as it turned out, there was something deeper here: that it was Carl and Gina who were really the actual parents, who should have been getting the child. The FGDM unearthed all of that, pulling the family together.”

Again in line with the FGDM process, the conference began with professionals (social workers, therapists and others) providing information to the family group. During the second part of the meeting, “family alone time,” when the family is left alone to come up with a plan for the child, “We all came up with sending him back with his parents,” said Carl.

In the next phase of the meeting, the family’s plan was presented to the professionals, who initially questioned its safety, because they had been under the impression “that I was on cocaine and had drinking problems,” said Carl. Everyone in the family insisted that these concerns were baseless. The professionals then said they were concerned about Gina’s condition, but, said Carl, “She hadn’t had a nervous breakdown in years. Her doctor wrote the judge about a thousand notes saying she was doing great.” Ultimately, the professionals approved the family’s plan to send Gino back home.

“The system had failed them,” said Joselyn. “Gina had a mental illness. It’s not a crime to have a mental illness. This happens all the time to people who are ill. They get abused, their rights trampled on. And Carl was denied custody of his son, because, according to him, ‘he had red eyes,’ and that meant that he was a drug addict. And in spite of all the documentation he had to the contrary, he was never listened to, so they got lost.”

FGDM facilitated Gino’s return home within six months. “It was the family that turned things around,” said Joselyn, adding, “FGDM was successful in bringing the extended family together, and they all recognized that he should be with his mom and dad. FGDM has its sights on really empowering families. No other approach in child welfare really takes that to heart.”

Carl was now able to help Gino with his “so-called ‘learning disability.’ They said, ‘He won’t focus.’ I said, ‘It’s not that he won’t focus, it’s that he can’t. Gino’s former failures were due to his being disciplined for inappropriate behavior, when he should have been coached. He had started thinking that he was the reason that he was in a foster home—that he was a bad kid. When you tell a kid that he’s been bad, subconsciously they start feeling guilty. And if they feel guilty, they say ‘I should be punished,’ and that’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“Eventually, Gino started coming around and getting better report cards. And pretty soon he started trusting me. He’d been gone for almost 10 years, so I had to gradually get him to come around. But once he did, it happened all at once. They said reunification would take a year, but it didn’t.”

Gino went from failing in school and “acting out,” due to stress and anxiety, to excelling in his school’s gifted and talented program and in chess, karate and skating. “Now that he’s back home with his parents, his problems are gone,” said Carl. “He’s on the honor roll and getting all sorts of awards for positive behavior. Ten years of trauma for Gino and surviving by adopting dysfunctional coping strategies could have been avoided with just one conference.”

Carl is now starting a support and training group to help parents and families with children in foster care and to promote FGDM. He envisions “a support group for fathers and families to come together to share their strengths, goals and concerns; training for parents to learn to communicate with social workers, judges, attorneys, therapists and foster parents, and to teach their children to motivate themselves, learn about stress and the consequences of stress-producing behavior; and ongoing coaching to assist with reunification and the skills necessary to distinguish the difference between inappropriate behavior and dysfunctional coping strategies.”

Concluded Carl, “Parents such as myself are human beings and American citizens, and we deserve the right to be treated as other than unfit. Gino asked me, ‘Why did God let all of those bad things happen to me?’ I answered, so you can help other children get out of foster care.”