News & Announcements

- Details

- Written by Lynn M. Welden

In the past, young people with behavioral, emotional and substance-abuse issues have been placed by school districts or local courts in alternative schools and community-based programs. But school districts in Pennsylvania, like those in many areas of the U.S. and other countries as well, have been under pressure lately to work with troubled students within their schools instead of sending them away.

- Details

- Written by Lisa Cook

St Edmund’s is a nursery and primary school that serves the North Lynn estate [urban housing]. North Lynn is an area of significant deprivation, unemployment, high alcohol and drug abuse and crime. Historically the school has faced many challenges and has been identified as a DCSF (Department for Children Schools and Families) “hard to shift” school. Standards at St Edmund’s are below the DCSF floor targets and have been so for the past nine years.

As a staff we feel passionate about children and making sure that their primary education is of high quality. Many of our children begin school with limited basic skills; their vocabulary, social skills and experiences are often very underdeveloped. Our children find engaging in learning and communicating with others difficult and find it very hard to take responsibility for their own behaviour.

- Details

- Written by Laura Mirsky

From New York City, USA, a high school social worker researching restorative practices as a way to build school community and improve student behavior

From San Francisco, California, USA, the director of a new prison dorm for war veterans hoping to learn restorative solutions for inmates

From São Paolo, Brazil, a community trainer working in the most violent urban neighborhoods refining her knowledge of restorative techniques

From Canberra, ACT, Australia, an education graduate student seeking ways to engage pupils

From Twin Falls, Idaho, USA, a juvenile corrections district liaison hoping to learn how to spread restorative practices statewide

From Louisville, Kentucky, USA, a teachers’ union representative checking out restorative practices on behalf of his school district

- Details

- Written by Lorenn Walker, Rebecca Greening

The Huikahi Restorative Circle is a group reentry planning process involving the incarcerated individual, his or her family and friends and at least one prison representative. This article in the June 2010 issue of Federal Probation provides a history and philosophy of this restorative practice, as well as outcome data regarding those who have participated in the process, which show extremely high participant satisfaction rates as well as significantly less recidivism than current state of Hawai''i and national rates.

- Details

- Written by Laura Mirsky

IIRP Class of 2010With friends and family looking on, 19 women and men received their degrees in restorative practices from the IIRP Graduate School, at the joyous commencement ceremony on June 19, 2010, in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA. Jill K. Dreibelbis, Eileen V. Hovey, Marlene Karen Ruby and Kate Burns Spokas Shapero received the Master of Restorative Practices and Education, and Roxanne Atterholt, Stacey Ann Bean, Christi L.Blank, Mardochee T. Casimir, Julia Maye Malloy, Sharon L. Mast, Ann Phoebe Moyer, Lynette Vineis Reed, Tami Beth Ritter, Mary Schott, Michele Wertz Snyder, John Douglas Tocado, Kelly L. Trzaska, Paul Jeffrey Werrell and Melinda Lappin Zipin received the Master of Restorative Practices and Youth Counseling.

IIRP Class of 2010With friends and family looking on, 19 women and men received their degrees in restorative practices from the IIRP Graduate School, at the joyous commencement ceremony on June 19, 2010, in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA. Jill K. Dreibelbis, Eileen V. Hovey, Marlene Karen Ruby and Kate Burns Spokas Shapero received the Master of Restorative Practices and Education, and Roxanne Atterholt, Stacey Ann Bean, Christi L.Blank, Mardochee T. Casimir, Julia Maye Malloy, Sharon L. Mast, Ann Phoebe Moyer, Lynette Vineis Reed, Tami Beth Ritter, Mary Schott, Michele Wertz Snyder, John Douglas Tocado, Kelly L. Trzaska, Paul Jeffrey Werrell and Melinda Lappin Zipin received the Master of Restorative Practices and Youth Counseling.

- Details

- Written by Laura Mirsky

Both Mexico and New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, are experiencing high incidences of crime and violence. To find new ways to deal with this issue, participants from both locations recently attended special four-day immersion events at the IIRP’s Bethlehem campus. An April 26-29 event involved 30 criminal and juvenile justice officials from 10 states in Mexico; a May 11-14 immersion included 15 educators and youth-justice professionals from New Orleans.

Tabasco State Attorney General’s Office: Manasés Sylvan Olan, Deputy Attorney General For Legal Processes; Rafael Miguel González Lastra, Attorney General; Mario Alberto Dueñas Zentella, Director of Training

Tabasco State Attorney General’s Office: Manasés Sylvan Olan, Deputy Attorney General For Legal Processes; Rafael Miguel González Lastra, Attorney General; Mario Alberto Dueñas Zentella, Director of Training

Both groups spent two days visiting the IIRP’s model program schools for at-risk youth, operated by Community Service Foundation and Buxmont Academy (CSF Buxmont), and two days training in restorative practices. The participants were very excited about what they observed and learned, and most are hoping to begin implementing restorative practices when they return home.

The seeds for the Mexicans’ visit were planted when John Bailie, IIRP director of trainers and lecturer at the IIRP Graduate School, presented a paper at the First International Restorative Justice Conference: Humanizing the Approach to Criminal Justice, in Oaxaca, Mexico, in September 2008. Subsequently, Nancy Flemming, coordinator of the alternative justice area of MSI’s (Management Systems International) Programa de Apoyo para el Estado de Derecho en México [Support Program for the Rule of Law in Mexico — PRODERECHO project, funded by USAID], organized the IIRP visit to help immersion attendees find ways to improve their respective states’ criminal justice systems. This undertaking was mandated by a 2006 amendment to the Mexican constitution requiring states to reform their penal codes to make them more effective and more humane — to include oral trials, the right to legal counsel and other legal prerogatives. Many of the immersion participants are involved in this reform process, in a variety of ways.

- Details

- Written by Laura Mirsky

Judy Happ, vice president for administration at the IIRP Graduate School and president of Community Service Foundation and Buxmont Academy, delivered the alumni commencement address at Shippensburg University’s School of Graduate Studies, in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, USA, on May 7, 2010. The following are excerpts from the address.

Judy Happ, vice president for administration at the IIRP Graduate School and president of Community Service Foundation and Buxmont Academy, delivered the alumni commencement address at Shippensburg University’s School of Graduate Studies, in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, USA, on May 7, 2010. The following are excerpts from the address.

I am vice president for administration for the International Institute for Restorative Practices Graduate School. We teach educators and others who work with children and youth to employ restorative practices in their work.

Restorative practices are processes and strategies for the development, repair or improvement of relationships, social capital and social discipline through collaborative empowerment.

- Details

- Written by American Humane Association and the FGDM Guidelines Committee

American Humane’s National Center on Family Group Decision Making, in coordination with the FGDM Guidelines Committee, has published Guidelines for Family Group Decision Making in Child Welfare, a comprehensive 63-page handbook covering all aspects of the FGDM process and philosophy, from basic explanations, history and values to detailed descriptions of the role of the coordinator, the referral process, preparation, the family meeting, follow-up and administrative support.

- Details

- Written by Laura Mirsky

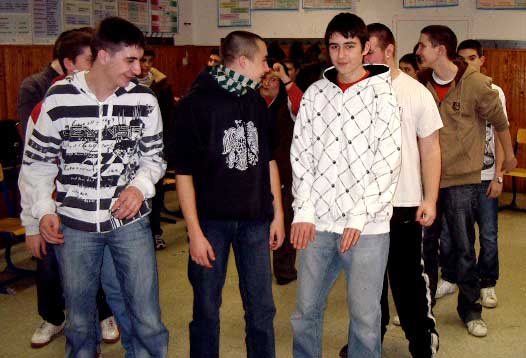

Hungarian high school students participate in a restorative exercise, forming a “boat” and “rowing” into the future, with their teacher at the center.In April 2010 Vidia Negrea, director of Community Service Foundation (CSF) Hungary, provided an introductory training in facilitating restorative conferences for four different youth group homes in Budapest. This is just the latest development in her work spreading restorative practices in Hungary, which also includes major efforts in schools and prisons.

Hungarian high school students participate in a restorative exercise, forming a “boat” and “rowing” into the future, with their teacher at the center.In April 2010 Vidia Negrea, director of Community Service Foundation (CSF) Hungary, provided an introductory training in facilitating restorative conferences for four different youth group homes in Budapest. This is just the latest development in her work spreading restorative practices in Hungary, which also includes major efforts in schools and prisons.

Psychologist Negrea came to Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, USA, in 2000 to learn about restorative practices and has never looked back. (See: www.iirp.edu/article_detail.php?article_id=NDUw, www.iirp.edu/article_detail.php?article_id=NDM0 and www.iirp.edu/article_detail.php?article_id=NTk1 for three articles which give a history of Negrea’s work bringing restorative practices to Hungary.)

Her recent work has been supported by the Ministry of Justice Hungary and the city of Budapest, including a project to reduce aggressive behavior in children and youth, which is bringing restorative practices to six big-city high schools.

- Details

- Written by IIRP

Script for facilitators of restorative conferences. Download PDF version.

Restorative Works Year in Review 2024 (PDF)

All our donors are acknowledged annually in Restorative Works.